The National Enameling and Stamping Company (NESCO)

The National Enameling and Stamping Company (NESCO) was a manufacturing company with factories in Granite City that was internationally famous for its graniteware cooking utensils in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. NESCO was instrumental in Granite City’s founding and early development as a national hub for iron and steelmaking.

Logo of NESCO when its product was known as Royal Granite Steel Ware.

From the Six Mile Regional Library

Origins

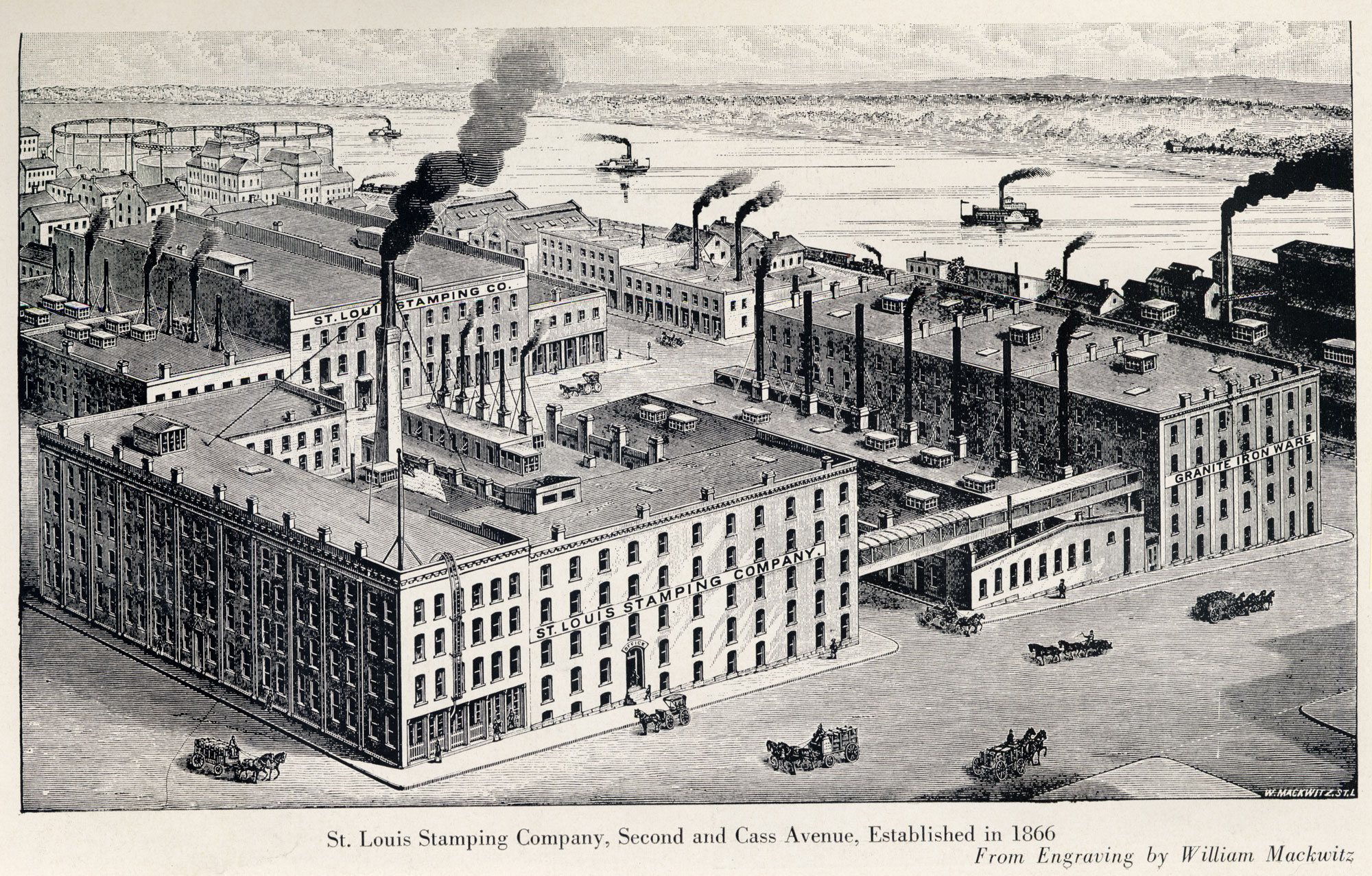

The company that would become NESCO was founded by Frederick G. Niedringhaus (1834-1922) and his brother, William F. Niedringhaus (1835-1908). Arriving in St. Louis in 1855, the Niedringhaus brothers were part of a large wave of German immigrants who arrived in the St. Louis region in the 1840s and 1850s. The brothers were tinsmiths, and in 1859 they began a tinworks in St. Louis that made household goods such as pots. In 1862 they mechanized production using a machine that stamped goods from a single sheet of tin. Business grew rapidly and in 1865 the brothers incorporated as the St. Louis Stamping Company. They built a large factory in St. Louis to produce tin products. (Lee I. Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company: The Early Years, 1899-1928 (Quad Right, 2005), 1.)

Engraving of the St. Louis Stamping Company’s factory at Second Street and Cass in St. Louis, circa 1886.

From the Six Mile Regional Library

The product that elevated the St. Louis Stamping Company into a nationally recognized brand was graniteware or “granite ironware,” the name given to metal utensils coated with an enameled surface composed partly of ground granite. Graniteware was discovered by William Niedringhaus while traveling in Europe. According to company lore, William saw similar pots and pans in a European shop window and then spent weeks and thousands of dollars at the factory to learn all he could about the graniteware process. William brought this knowledge back to St. Louis and in 1874 the Niedringhaus brothers began manufacturing graniteware in their St. Louis plant. The St. Louis Stamping Company received patents for graniteware in 1876 and 1877. Although the iron and tin used by the company was originally imported, the Niedringhaus brothers built their own iron works in St. Louis in 1878 named the Granite Iron Rolling Mills. In the late 1880s, William successfully developed a process to enamel tin. (Previously, only iron could be enameled.) The Granite Iron Rolling Mills soon began producing tinplate alongside iron. (David DeChenne, “A Progressive Era Mill Town ‘Where the Laboring Man [Was] King,’” Locus 4, no. 1 (1991): 1; Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 1-5.)

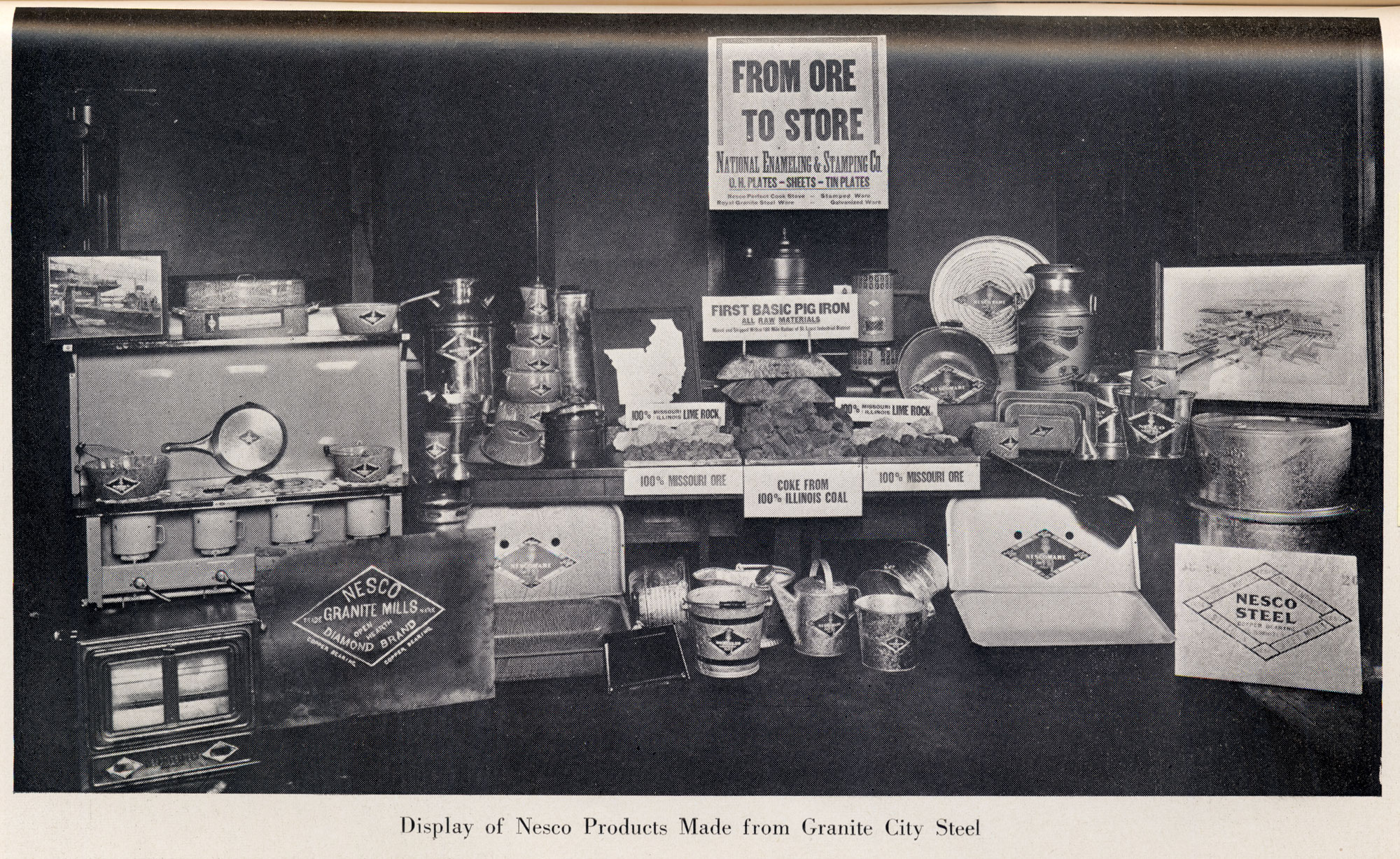

This display shows various products made by NESCO, such as a stove, frying pans, milk pans, buckets, roasters, watering cans, and a steel barrel. It also emphasizes that the ore used in NESCO products came from Illinois and Missouri.

From the Six Mile Regional Library

Political influence was also key to NESCO’s success in the late nineteenth century. Both Niedringhaus brothers were involved in politics. Frederick Niedringhaus was an influential Republican member of Congress from 1889-1891 who focused on raising tariffs to protect his company’s profits. A newspaper at the time referred to him as “a protectionist of the most pronounced kind.” (“Lament of the Spoilsmen,” New York Times, April 28, 1890.) Specifically, he focused on raising the tariff on imported tinplate that competed with tinplate produced by the Niedringhaus firm. In Congress, Frederick was a vocal backer of the 1890 McKinley Tariff, which more than doubled the duty paid on foreign tinplate.

Move to Granite City

With business booming thanks to a growing market for graniteware, protective tariffs, and new innovations, the St. Louis Stamping Company and the Granite Iron Rolling Mills needed to expand in the 1890s. The Niedringhaus brothers soon settled on a site in Madison County for their new plant. They chose a site of 3,500 acres located near the Illinois entrance to the new Merchants Bridge. (DeChenne, “A Progressive Era Mill Town,” 1; Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 5.) Many factors convinced the Niedringhaus brothers to relocate the company to Madison County. Farm land on the east side of the Mississippi River was inexpensive compared to St. Louis, there was good access to transportation by water and rail, costs for taxes, fuel, and power were moderate, and there was a steady supply of laborers nearby. The site could also be reached quickly from downtown St. Louis, where the Niedringhaus brothers kept their offices. (David E. Cassens, “The Bulgarian Colony of Southwestern Illinois, 1900-1920,” Illinois Historical Journal 84, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 16.)

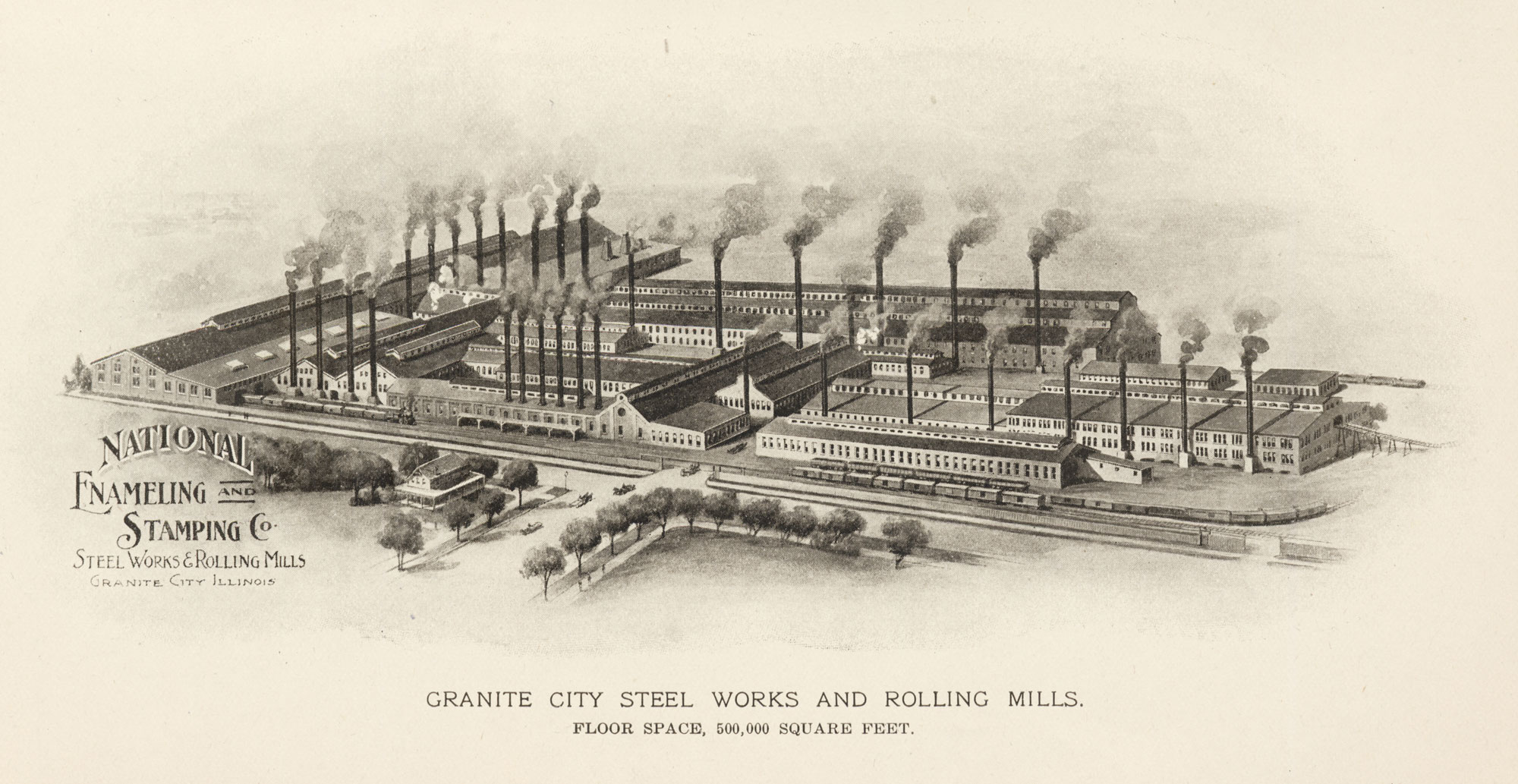

NESCO’s steel works and rolling mills in Granite City in 1903.

From the Six Mile Regional Library

The new city created for the Niedringhaus works was named Granite City in honor of the company’s famous product. Rejected alternatives included Tinville and Niedringhaus. (Six Mile Regional Library District, “National Enameling & Stamping Company: A Brief History,” Six Miles of Local History; Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 5.) In addition to planning for their manufacturing plants, the Niedringhaus brothers set up a new city by building roads and homes and planting trees. In 1894, the Niedringhaus brothers sold off excess land that they would not need for their factories. This “excess land” became Granite City. Enameling and stamping plants and large mills began running in 1895. These huge mills were the town’s main employers and the symbolic heart of the city. The Niedringhaus brothers also provided financial support for two other steel companies in Granite City: the American Steel Foundry and Commonwealth Steel. Granite City soon became known nationwide as an iron and steelmaking city on par with Gary, Indiana, and Homestead, Pennsylvania. Granite City formally incorporated as a city in 1896. Granite City’s rapid transformation from farmland to industrial hub amazed observers. A 1912 history declared, “Where only a decade ago was heard only the rustling of the wind through the corn blades now resounds the clangor of steel manipulated by the sons of Vulcan.” (W. T. Norton, ed., Centennial History of Madison County, Illinois and Its People, 1812 to 1912 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing, 1912), 579.)

While many towns that grew around steel mills became company towns in this era, Granite City was never controlled by NESCO officials. This was due to the powerful union that organized early on at NESCO plants and the Niedringhaus brothers’ willingness to work with organized labor rather than root them out as other steelmakers did during these years. (DeChenne, “A Progressive Era Mill Town,” 2-10.) NESCO’s factories were the heart of Granite City in the first decades of the twentieth century. The company employed 2,400 workers and its plants sprawled over 33 acres. (Six Mile Regional Library District, “National Enameling & Stamping Company: A Brief History.”) Like most major steelmakers in the early twentieth century, the Niedringhaus brothers built housing for workers to alleviate shortages. But few steel firms were interested in going into the real estate business. After building the homes, the Niedringhaus firm sold the houses to employees at cost plus six percent interest.(David Brody, Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era. (Harvard University Press, 1960), 87-88.) Granite City’s municipal government was run by those affiliated with the Niedringhaus brothers during its early years. This changed in the first decade of the twentieth century, however, as candidates affiliated with labor unions ran for city offices and eventually took control of city government. The Niedringhaus firms acted as Granite City’s major employer, but did not entirely dominate other industrial ventures that wished to set up in the city nor did they control the lives of workers beyond the shop floor.

NESCO’s Creation and Heyday

In 1899, the St. Louis Stamping Company and Granite Iron Rolling Mills combined with several other companies producing enameled iron and tin products around the country. The new combination, named the National Enameling and Stamping Company (NESCO) to reflect its nationwide reach, established its headquarters in New York City under president Frederick G. Niedringhaus. NESCO expanded nationwide in these years. Although its Granite City plant remained a crucial component in its business, it acquired new plants in Baltimore and New Orleans. NESCO’s graniteware products were known around the world in the early twentieth century and were prominently featured at a display at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The company’s signature product went through several name changes in this period, from Granite Ironware to Royal Granite Steel Ware to Royal Granite Enameled Ware, and eventually Nescoware. (Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 6-12.)

NESCO’s exhibit in the Palace of Manufactures at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis

From the Six Mile Regional Library

Immigrant workers were central to NESCO’s business. In the 1870s, the St. Louis Stamping Company imported skilled Welsh and English workers to their St. Louis tin and iron works. After relocating to Granite City, Bulgarian workers became crucial to the unskilled labor force at NESCO and other steel mills in Granite City. As many as fifteen thousand Bulgarian immigrants lived in or near the NESCO plant by 1911. The Tri-Cities area was considered the major center of Bulgarian immigration into the United States in the early twentieth century. (William P. Dillingham, et al. Reports of the Immigration Commission (Government Printing Office, 1911), 496; Cassens, “The Bulgarian Community of Southwestern Illinois, 1900-1920,” 15.) Granite City’s steel mills worked with leaders of the Bulgarian immigrant community to ensure that all Bulgarian immigrants received jobs. (Brody, Steelworkers in America, 109.) Immigrants in Granite City arrived and left in sync with the business cycle. During the economic depression of 1908, for instance, nearly 90 percent of the Bulgarian immigrants who worked in Granite City’s steel mills returned to their homeland. (Ibid., 106.) The most prominent immigrant neighborhood for mill workers in Granite City was Lincoln Place, earlier known as Hungary Hollow. While NESCO’s immigrant workers mostly followed patterns laid down in other steelmaking cities, there were some unique variations. For instance, Bulgarian immigrant workers in Granite City were known to save on boarding costs by doing their own housekeeping. (Ibid., 98.)

A Granite City union, Good Friday Lodge No. 8 “Granite Burners”, on the steps of the Granite City Post office in 1906. The lodge was part of the Amalgamated Association of iron, steel, & tin workers.

From the Six Mile Regional Library

NESCO’s workforce was unionized soon after the company was founded. Lodge 11 of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers was founded in Granite City in 1899. (Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 12.) Three lodges of the Amalgamated existed in Granite City by 1900: Granite City no. 11, Granite City no. 16, and Good Friday no. 8. Granite City lodge no. 11 was the heart of the city’s union power. This lodge represented workers in the hot mill. Their work required skilled craft knowledge and was not automated until well into the twentieth century. Thus, they commanded a central position in NESCO operations. (DeChenne, “A Progressive Era Mill Town,” 4-5; Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 13.) Lodge no. 11 grew in membership and power in the first decade of the twentieth century, a period when the Amalgamated was being wiped out elsewhere in the American steel industry. Unlike major steelmakers such as Andrew Carnegie and U.S. Steel, the Niedringhaus brothers chose to work with the Amalgamated union rather than drive them out of their factories. This was likely motivated in part by their dependence on skilled labor and limited production facilities. It was easier to work with the union than to attack it. By 1912, NESCO was described as “one of the most strongly unionized steel producing plants in the country.” (Quoted in DeChenne, “A Progressive Era Mill Town,” 6.) Strikes and walkouts were thus extremely rare at NESCO. There were no major strikes during the Progressive Era and only a few isolated wildcat actions.(DeChenne, “A Progressive Era Mill Town,” 8-9.)

Three workers inside NESCO’s steel works and rolling mills, circa 1914.

From the Six Mile Regional Library

NESCO played an important role in World War I by producing heavy steel plates for armoring battleships and enameled goods for soldiers. NESCO’s Granite City facilities were at the peak of their production and influence immediately after the war. In 1919, the company’s production facilities in Granite City sprawled over 112 acres and included ten open-hearth furnaces, a plate mill, and twenty-four sheet and tin mills. The company’s profits in these years soared to nearly six million dollars. NESCO also benefited from foreign competition for enamelware being cut off during the war. The company’s Granite City facility expanded rapidly at this time. In 1921, NESCO opened a large steel mill in Granite City. Yet the massive expansion failed to pay off and by the mid-1920s the company was losing money. (Niedringhaus, National Enameling and Stamping Company, 18-20.)

Later Years and Closure

Due to problems from the expansion into steelmaking in the early 1920s, NESCO was split up. During 1927-1928, NESCO’s steelmaking operations were split away from the traditional enamelware operations to become Granite City Steel Company. NESCO continued to operate its enamelware business. NESCO struggled to adapt to a marketplace that was changing rapidly in the 1930s and 1940s. Its traditional enamelware was surpassed by new cookware using nonstick coatings and made from aluminum. One successful product was the NESCO roaster, which was developed by employees in Milwaukee in the 1930s. The roaster was created by electrifying a NESCO double boiler and the product was sold door-to-door. In the 1950s, NESCO was purchased by Knapp Monarch Company but it remained on the verge of failure. (Ibid., 20.)

The NESCO building in 1929. Accross the street on the left is the Union Depot Building.

From Mark Eddleman and the Six Mile Regional Library

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation, which owned NESCO at the time, announced the closure of NESCO’s Granite City plant in February 1956. The closure was blamed on market conditions in the electrical appliance market at the time. About six hundred employees worked at the plant by 1956. Officials in Granite City tried to keep the plant running but were unsuccessful. The company was officially defunct as a separate entity in 1956, thus closing more than sixty years of industry in Madison County.

After 1956, the NESCO facility in Granite City was used for storage. The warehouse stored ammunition, tires, and scrap metal, among other items. NESCO’s buildings went up in flames on October 27, 2003. The giant fire was one of the largest in Madison County history and destroyed the remnants of this once-great company. A brick tower was all that survived the fire, but it was demolished on November 12, 2003, due to damage from the fire. (Paul Hampel, “Blaze Destroys Historic Warehouse,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 28, 2003; Paul Hampel, “Wrecking Ball Razes Tower,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 13, 2003.)