Lynching of Robert Prager (1918)

Collinsville was the site of the only lynching of a German immigrant on American soil during World War I. Robert Paul Prager (1888-1918) was lynched by a mob of approximately one hundred men and boys just after midnight on April 5, 1918, atop a hill on St. Louis Road. His lynching came at a time when anti-German hysteria swept across the United States, much of it fed by federal government propaganda.((Peter Stehman, Patriotic Murder: A World War I Hate Crime for Uncle Sam (Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2018).)) Prager had been accused of planning to sabotage a coal mine and of being a socialist and a German spy. None of the accusations were proven true. Twelve men were later charged with Prager’s murder, but eleven were acquitted by a Madison County jury in less than ten minutes.((St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 2, 1918.)) The twelfth suspect was never located and charges against him were dismissed.

Background

Collinsville, a town of approximately ten thousand residents in 1918, was a largely a coal-mining community at the time, with nine mines in or surrounding the city. Coal miners made up more than 50 percent of the working-male population and members of the United Mine Workers dominated the community. There was labor radicalism, as evidenced by a series of wildcat strikes against the coal mines and an attempt to shut down the adjacent St. Louis Smelting and Refining (lead) plant when it tried to stop its workers from unionizing.((Stehman, Patriotic Murder.)) But coal was also an important part of the national economy and war effort, and state coal production would never be higher than it was in 1918.((Illinois Department of Mines and Minerals, 37th Annual Coal Report of Illinois: 1918.))

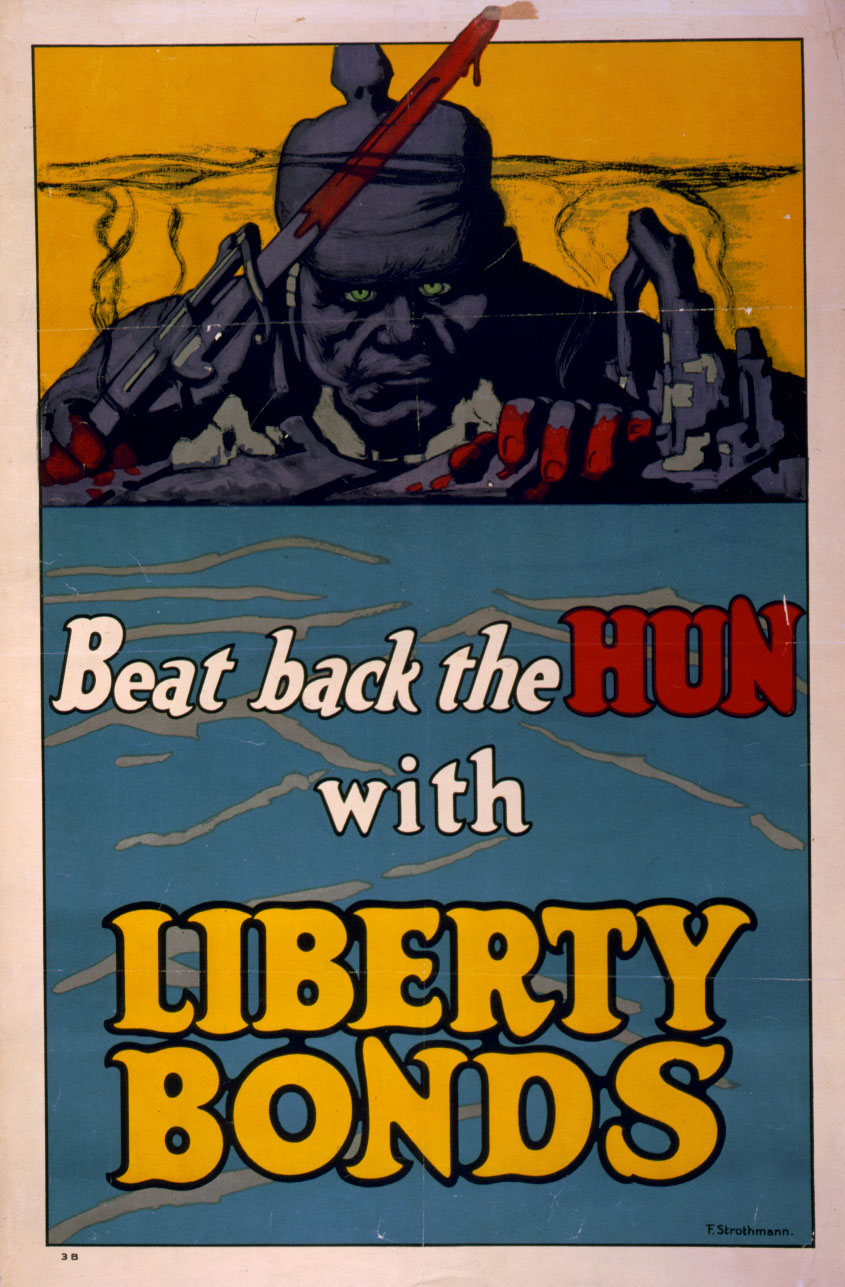

After the United States joined in the fight against Germany in the Great War in 1917, the federal government under President Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) to help win public support for the war in a nation which had seen the arrival of twelve million immigrants since the turn of the century.((David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, 25th anniversary ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).)) The CPI essentially became a propaganda agency which helped whip the nation into a patriotic frenzy, in addition to producing promotional materials for military recruitment, war bond drives, and food and fuel conservation. Besides serving Uncle Sam, a central theme of all the CPI’s ads, posters, booklets, and flyers was the demonization of Germany and warning of the threat German spies posed in America.((Alan Axelrod, Selling the Great War: The Making of American Propaganda (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009).))

This 1918 poster, produced by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, was among many that demonized Germany during World War I.

From the Library of Congress

Collinsville became caught up in the patriotic frenzy too, from parades on the first draft registration day to nearly constant patriotic programs and fundraisers. The Red Cross women knitted sweaters while seemingly every other club or lodge was doing its part to support the men going “over there.”

Nationwide there were threats and violence against those who were suspected of being pro-German and those who opposed the war for any reason, including religious beliefs. Many German immigrants or those of German ancestry particularly were singled out. German street names were changed, schools stopped teaching the German language, and German books were burned.((H. C. Peterson and Gilbert C. Fite, Opponents of War, 1917-1918 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1957).)) The U. S. government in 1917 introduced the Espionage Act, but many thought it did not go far enough to suppress those who opposed the war.((Kennedy, Over Here.)) Groups such as the American Protective League were formed to encourage citizens to be on the lookout for German spies.

No threat was deemed too implausible. Guards were posted near a Belleville flour mill for fear that German spies would poison the flour. Secret Service officials interrogated a Staunton schoolboy and his father after the boy refused to salute the flag.((Stehman, Patriotic Murder.)) Nationwide, those under suspicion and harassed by mobs or other groups were made to kiss the flag, beaten, tarred and feathered, or otherwise tormented. It was not uncommon for citizens to take the law into their own hands in the era, and the lynching of blacks was sadly prevalent.((“Lynching and Mob Murders, 1917,” Crisis, February 1918.))

There was a significant increase in violence in early 1918 in southern Illinois, much of it playing out in the coal fields where union and ethnic rivalries also entered into the equation. Locally, a number of men had been made to show their patriotism, usually after saloon deliberation found them of questionable loyalty.((Stehman, Patriotic Murder.))

Robert Prager arrived in the United States in 1905 at age 17. Born in Dresden, Germany, he listed his occupation as baker. Much of Prager’s background in America is unknown, but he did spend time in jail for stealing a suit of clothes in northern Indiana. Prager drifted about the Midwest, landing at bakers’ jobs in Nebraska in 1915. By 1916 he had drifted into St. Louis, where another baker took him in. One year later, as the United States declared war on Germany, Prager became fiercely patriotic to this country. He applied for his U. S. citizenship the day after President Wilson’s war speech to Congress. Prager attempted to enlist in the Navy but was refused due to blindness in one eye.((Ibid.))

Prager in Collinsville

Robert Prager moved to Collinsville later in 1917, taking a job at Bruno Bakery. There he learned of the high wartime wages that coal miners were earning, and he obtained a job as a laborer at the Donk Brothers’ #2 mine in nearby Maryville. But Prager most wanted to work as a miner, given their higher wages. Prager applied to join the United Mine Workers Local 1802, but he had made enemies in the local and it refused his application for membership, perhaps due to his Socialist views or the union believed he was pro-German. On April 3, 1918, the Maryville miners made Prager the center of a patriotic parade near saloons in that village just north of Collinsville.((East St. Louis Daily Journal, April 5, 1918.)) Rejection by the miner’s union meant Prager could not work as a coal miner and he was warned to leave the area.

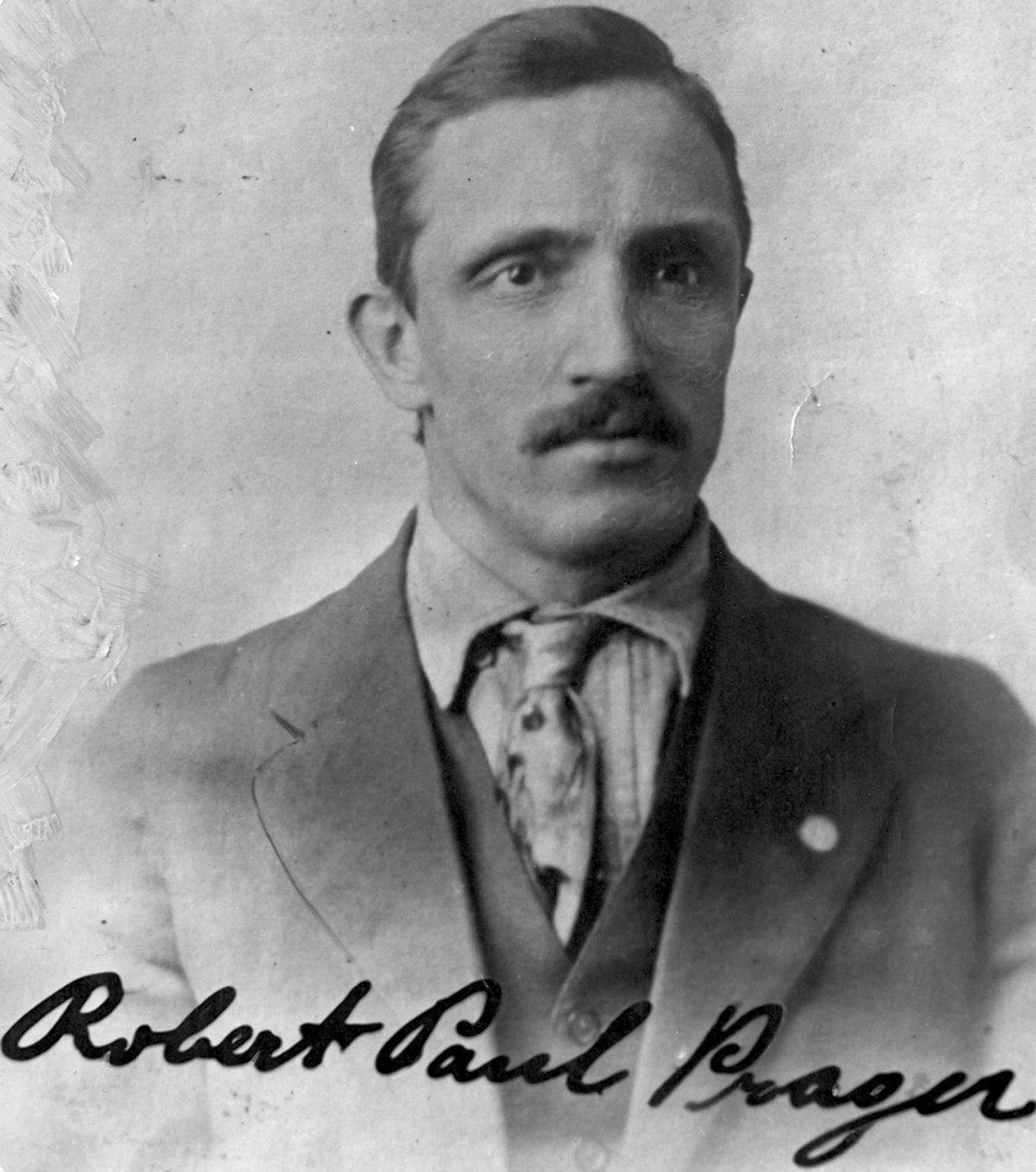

This photo of Robert Prager was stolen his home following his lynching.

Photo from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch photo archives

Prager, obstinate and argumentative, drafted a letter of protest to the miner’s local, claiming he had been treated unfairly by Local 1802 President James Fornero. In the letter, Prager said, “I ask in the name of humanity to examine me to find out what is the reason I am kept out of work,” and added, “I am heart and soul for the good old USA. I am of German birth, of which accident I cannot help.”((St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 6, 1918.)) He posted the letters near the Maryville saloons and mine. Finding the messages on April 4, 1918, as they exited the mines, the men were incensed at Prager.

Maryville miners went to Collinsville in search of Prager that evening. After meeting with other miners at a Collinsville saloon, about 75 men went the short distance to Prager’s shack and ordered him to leave town within ten minutes.((St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 31, 1918.)) The men then decided to parade Prager past the Main Street saloons before he left and to make him kiss the flag. “All right brothers, I’ll go,” Prager said, “if you don’t hurt me.”((St. Louis Times, May 31, 1918.)) The diminutive Prager was paraded to Main Street as the crowd grew larger, all the while men and boys taunting and harassing the German immigrant. He was told to remove his shoes and hang them around his neck, while he was wrapped in the American flag and ordered to sing patriotic songs.((St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 7, 1918.)) Collinsville Mayor John Siegel saw the mob twice, the second time noting its temperament had become more hateful and mean spirited.((Collinsville Herald, April 5, 1918.))

Mayor Siegel called city police and asked the officers to protect the man from the mob. Officers ran four blocks after the mob and took Prager back to their police station in City Hall. The mob mostly dispersed, but some remnants of the group reassembled a half block from City Hall and complained of Prager being taken from them. The crowd grew larger when the mayor ordered the saloons closed and more men poured into the intersection of Main and Center streets.((Edwardsville Intelligencer, April 5, 1918.)) There was an argument as to whether the men should go home or get Prager from the police station. When a flag was brought forward and the crowd began singing The Star-Spangled Banner, the issue was decided and the mob moved to the front of City Hall.

Mayor Siegel spoke from the top steps of City Hall, along with other city leaders, trying to convince the men to let them turn Prager over to federal officials, so he might be interviewed and get a fair trial.((Collinsville Herald, April 5, 1918.)) The crowd had grown to about three hundred as the debate raged in front of City Hall. In an ill-thought plan to quietly remove Prager from City Hall, police officers hid the immigrant in a clay sewer tile after taking him from a jail cell.((Ibid.)) One officer soon told the mayor that Prager had been taken away by federal officials. As the mob, mostly drunken, became more menacing, the mayor agreed to let the men search City Hall, believing Prager was gone from the building. The first search by the mob came up empty, but a second search yielded Prager hidden in the sewer pipe. He was brought from the City Hall basement by Wesley Beaver and Joe Riegel, while the police officers did nothing.((Belleville News-Democrat, April 11, 1918.))

Lynching

Prager was marched back to Main Street, where the harassment began anew. The flag was brought forward to lead the procession as the parade started again, marching Prager west on Main Street, then west on St. Louis Road. Along the route, Prager was beaten and tormented by the men and boys and shown off to those in streetcars and automobiles. When the mob of about one hundred reached Bluff Hill on St. Louis Road, the procession stopped and after some discussion a car was dispatched to obtain tar for Prager to be tarred and feathered.((St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 12, 1918.))

But the car returned in a few minutes, unable to find tar. The vehicle did contain a rope, however, and it was taken from the car by Joe Riegel and placed over a sturdy limb of a hackberry tree.((St. Louis Star, April 5, 1918.)) Prager was taken to the tree and offered an opportunity to pray, which he knelt and did in his native German. After repeated pleas from Riegel, other men came to the rope to assist the mob leader in lifting Prager from the ground.((St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 19, 1918.)) But the mob had neglected to tie Prager’s hands and he lifted himself up on the rope. When lowered to the ground, Prager was once again interrogated by the men and asked if he wanted to write a note to his family. Prager did, writing (in German), “Please pray for us my dear parents,” and saying it was his last letter.((Carmen Freeman translation.)) With his hands this time tied behind his back, Prager was raised again about ten feet into the air and died some minutes later.((St. Louis Star, April 11, 1918.))

Arrests

A coroner’s jury charged five men with murder the following week. They were: Wesley Beaver, 26; William Brockmeier, 41; Richard Dukes, 22; Enid Elmore, 21; and Joe Riegel, 28. The leader in taking Robert Prager from City Hall and in the lynching atop Bluff Hill, Joe Riegel, gave remarkably candid comments to both the coroner’s jury and a reporter from a St. Louis newspaper just prior to his testimony.((Belleville News-Democrat, April 12, 1918.)) A Madison County Grand Jury in late April returned murder indictments against the five men previously arrested, and seven others. They were: Charles Cranmer, 20; George Davis, age unknown; James DeMatties, 18; Frank Flannery, 19; Calvin Gilmore, 44; John Hallworth, 43; and Cecil Larremore, 17.((St. Louis Star, April 27, 1918.)) All but Davis were taken into custody, who remained at large until charges against him were eventually dropped.

Trial

After a two-week process where more than seven hundred men were summoned to find an unbiased jury, opening statements for the trial were heard on May 27, 1918, at the Madison County Courthouse in Edwardsville.((Edwardsville Intelligencer, May 28, 1918.)) The trial was marked by numerous attempts to impugn Prager’s patriotism and few witnesses were willing to provide conclusive testimony as to what had occurred less than two months earlier.((Stehman, Patriotic Murder.)) The defendants, including Joe Riegel, recanted incriminating statements they had made earlier.((St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 31, 1918.)) After impassioned closing arguments from each side, the case was given to the jury. But not before a military band, in town for a sendoff of departing soldiers, played patriotic songs in the courthouse atrium. In less than ten minutes, the jury returned not guilty verdicts for all defendants, with one juror remarking, “I guess nobody can say we aren’t loyal now.”((Chicago Civil Liberties Committee, Pursuit of Freedom: A History of Civil Liberty in Illinois, 1787-1942. (Chicago: Chicago Civil Liberties Committee, Illinois Civil Liberties Committee, 1942).))

The 11 men accused of killing Robert Prager stand in front of the Madison County Courthouse in Edwardsville on May 14, 1918, when jury selection began. Wesley Beaver stands far left in the front, and leader Joe Riegel is in the back, second from the left. The 12th man, sheriff’s deputy Vernon Coons, stands at the far right in the back and was their escort.

Photo by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Both the lynching and the trial verdict received widespread criticism. “The new unwritten law appears to be that any group of men may execute justice, or what they consider justice, in any case growing out of the war,” the New York Times said.((New York Times, June 3, 1918.)) “The lynching of Prager was reprehensible enough in itself, but the effort to excuse it as an act of ‘popular justice’ is worse,” said the Chicago Daily Tribune.((Chicago Daily Tribune, June 5, 1918.)) The reaction by President Wilson was muted. Although he had spoken out earlier against mob rule, he would not make a formal statement condemning lynching until nearly two months after the verdict. “How shall we commend democracy to the acceptance of other peoples if we disgrace our own by proving that it is, after all, no protection to the weak?” Wilson said.”((Library of Congress, Wilson Proclamation of July 26, 1918.))