Route 66 in Madison County

U.S. Highway 66 was designated across eight states on November 11, 1926, as part of the federal numbered highway system. Approximately 300 miles of the new 2,448-mile U.S. highway slashed across Illinois from Chicago to the Mississippi River, including close to 40 miles in a diagonal path from northeast to southwest across Madison County.

The history of Route 66 in Madison County actually began before the official designation date, due to the stepped-up efforts of the State of Illinois to construct several thousand miles of paved highway during the early 1920s. Over the next four decades, the famous Chicago-to-Los Angeles route was altered through Madison County as the volume of traffic increased, demanding straighter, faster alignments.

National Highway Milestones

The Good Roads Movement began in the late 1800s with bicyclists who were tired of getting stuck in the mud. With the introduction of the automobile, the movement grew into political action to lobby for paved roads.((Brockton G. Lange, History of the Illinois Department of Transportation 1903-2013 (Springfield: Illinois Department of Transportation, 2013), 9-10.)) President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Aid Post Road Act in 1916 with the intent of purposing roads for military use and improving rural mail delivery.((Lange, 13.))

The American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) adopted the federal numbered highway system on November 11, 1926, establishing the use of odd numbers for north-south highways and even numbers for east-west highways.((Richard F. Weingroff, “From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the U.S. Numbered Highway System.” U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Highway History.))

The U.S. Highway 66 Association formed in April 1927 to promote the use of the eight-state highway from Chicago to Los Angeles and encourage those states to pave their sections as quickly as possible.((Susan Croce Kelly, Father of Route 66: The Story of Cy Avery (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), 192-195.)) The State of Illinois, however, already had a paved direct route from Chicago to East St. Louis which was ready and available to accept the national highway designation.

State of Illinois Highway Milestones

In 1903, the Illinois General Assembly authorized Governor Richard Yates Jr. to appoint a three-man non-salaried Good Roads Commission and appropriate $5,000 for the state to determine the present state of the roads and study how to proceed. The report was presented in 1905, colored by the harsh winter conditions of 1903-1904.((Lange, 4.))

The State Highway Commission was formed in May 1905 by the 44th General Assembly, marking a turning point away from county and township autonomy over the roads.((Ibid., 5)) The 45th General Assembly passed the first Illinois Motor Vehicle law in 1907 to define a motor vehicle, require drivers to register with the Secretary of State, and establish a speed limit.((Ibid., 6 – 7))

The Tice Road Law of 1913, named after Homer J. Tice, an Illinois Good Roads supporter, finally established the State Highway Department. Funding could then flow to county superintendents for road construction and maintenance. The new Illinois Division of Highways was responsible for the design, construction, maintenance, and testing of both state bond issue roads and federal-aid roads within the state.((Ibid., 12))

The department chose a two-mile stretch west of Springfield at the village of Bates for a test road. Between the summer of 1920 and early 1921, personnel constructed a test road with 64 different paving combinations before driving trucks over the test sections to determine the load capacity. The results of the Bates Test Road dictated policy in early highway paving throughout the state.((Ibid., 19))

Extensive testing on the Bates experimental road demonstrated the need for enforcement load limits. In 1921, the 52nd General Assembly of the State of Illinois directed the Department of Public Works and Buildings to hire State Highway Patrol officers to enforce the state’s motor vehicle law. The Illinois State Police was officially established in 1922, and the troopers began to patrol for trucks that were overweight on the new slab highways.((Ibid., 20))

With a growing Illinois population, the promise of post-war prosperity, and a successful campaign to “pull Illinois out of the mud,” voters in November 1918 passed a $60 million state bond issue for road construction.((Ibid., 18)) In 1919, the State of Illinois received funding from the Federal Aid System for five roads, including the Chicago-Springfield-East St. Louis Road, portions of which would become State Road 4 (SR4).((Dorothy R. L. Seratt and Terri Ryburn-Lamont, “Historic and Architectural Resources of Route 66 Through Illinois,” National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service), 12.)) By the end of 1926, all of the $60 million State Bond Issue was contracted, and SR4 had been constructed from Chicago to East St. Louis.((Frank T. Sheets, “Road Construction in Illinois,” Illinois Blue Book 1927-1928 (Springfield: Office of Secretary of State, 1927-1928), 322; “1,000 Miles of Road Scheduled for Construction in Illinois,” Edwardsville Intelligencer, December 20, 1926.))

The SR4 pavement was ready and waiting in 1926 to carry U.S. Highway 66. The section from Springfield south upon SR4 was planned to be a temporary route. In 1930, a new, straighter alignment was built a few miles east of the SR4 route through Sangamon, Montgomery, Macoupin, and into Madison County. This new alignment was constructed specifically for Route 66 and went through fewer towns, allowing faster travel.

The Madison County Section

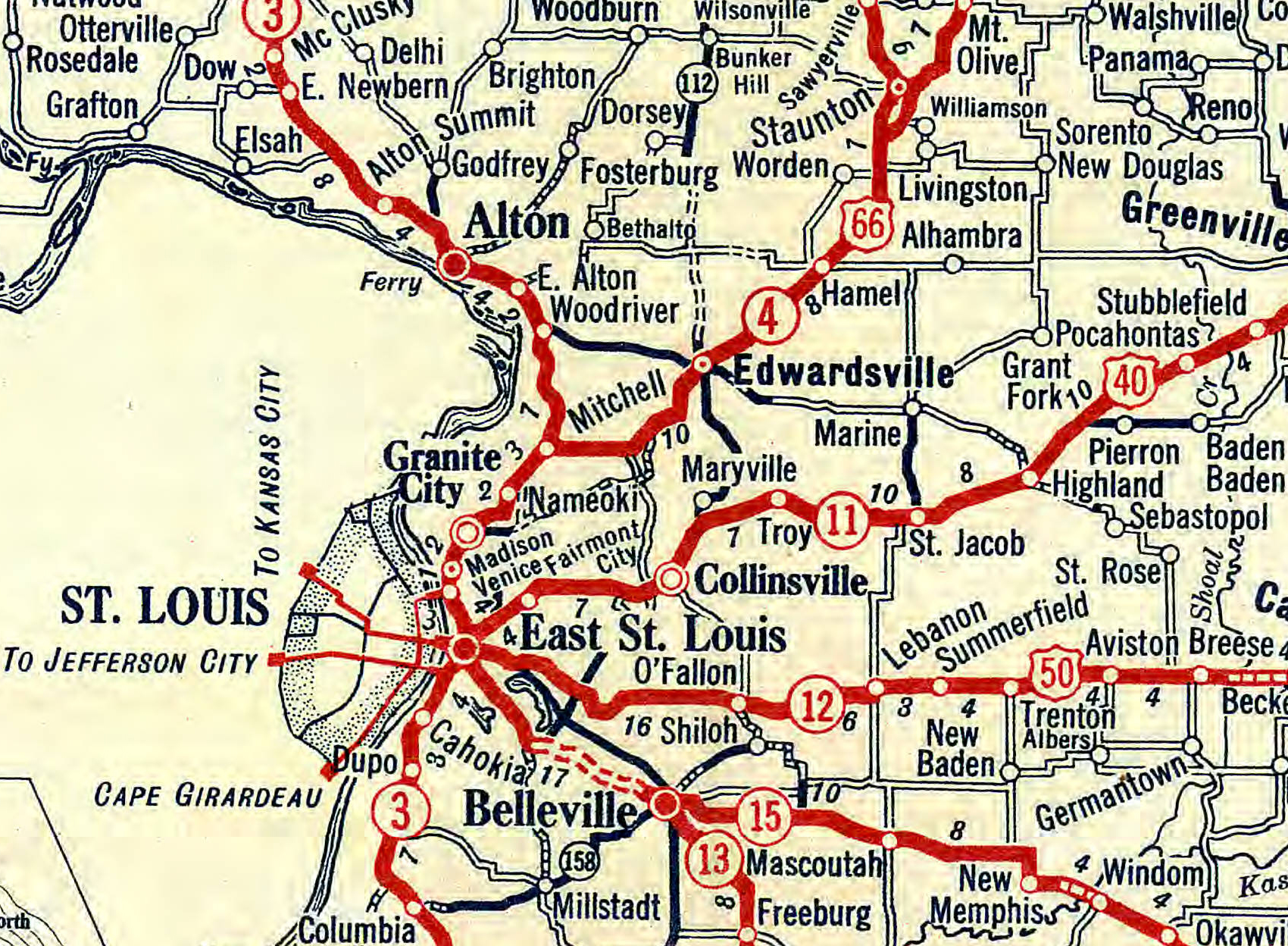

This subsection of a 1928 Illinois highway map shows the original route of Route 66 through Madison County.

From the Illinois State Highway Maps collection of the Illinois Digital Archives

In Madison County, the U.S. Highway 66 designation upon SR4 spanned close to 40 miles from the Macoupin/Madison County line to the Mississippi River. The route entered the county just south of Staunton and flowed generally southwest through Hamel, Edwardsville, Mitchell, Nameoki, Granite City, Madison, and Venice to cross the Mississippi River on the McKinley Bridge.((Illinois Official 1927 Highway Map (Springfield: Illinois Secretary of State); Illinois Official 1928 Highway Map (Springfield: Illinois Secretary of State).))

In 1929, the route was altered slightly near the river to cross the Municipal or “Free” Bridge from East St. Louis in St. Clair County; the older route over the McKinley Bridge was marked “Optional 66.”((Joe Sonderman, Route 66 in St. Louis (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 47.))

In the early 1930s, the new alignment south from Springfield brought Route 66 into Madison County from the east side of Staunton instead of from the west side. The new highway skirted the eastern edge of Livingston on its way to Hamel, where it joined the 1926-1930 alignment.

The $2 million Chain of Rocks toll bridge across the Mississippi River opened on July 20, 1929, to provide access back and forth to the north side of St. Louis. The Illinois approach to the bridge was prepared with new pavement from Mitchell west to the bridge, but Missouri did not yet have an improved route for the new alignment. Consequently, the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) did not move the U.S. Highway 66 designation until the mid-1930s to continue west from Mitchell across the new bridge. The original alignment from Mitchell south through Nameoki and Granite City was then named City Route 66 due to its entry across the river into downtown St. Louis.((“Chain of Rocks Highway Toll Bridge Opened,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 21, 1929; Sonderman, 57-58.))

During the winter of 1937-1938, the Illinois Division of Highways considered re-routing the highway through Edwardsville onto different surface streets due to safety concerns; the Edwardsville High School, completed in 1928, fronted onto the West Street section of Route 66. The city and its businessmen fought the re-routing for two reasons: traffic would bypass the business district, and the downtown streets which were almost destroyed by twelve years of heavy highway traffic would not be reconstructed with federal money, but would be the responsibility of the city to rebuild. The Division abandoned the plan in May 1938, revealing that Edwardsville would be bypassed by the mid-1950s with a newly-constructed alignment whose path would shoot straight from north of Hamel to Collinsville. In the spring of 1939, Madison Construction Company began pulverizing the brick paving through Edwardsville, followed by concrete repaving, using available federal funds.((“Early Agreement Needed,” Edwardsville Intelligencer, December 30, 1937; “State Division Orders Changes in Route 66 Here; Requires use of Schwarz-Benton Streets, But Will Rebuild St. Louis-West [Streets] if City Officials Cooperate,” Edwardsville Intelligencer, May 20, 1938; “State Reverses Decision on 66; Division of Highways Gives up Plans to Change Course over Schwarz Street,” Edwardsville Intelligencer, May 26, 1938.))

As promised by the Illinois Division of Highways, in the mid-1950s a new alignment of freeway-type construction destined to become Interstate 55 bypassed Hamel and Edwardsville. The new pavement beginning above Hamel merged with U.S. 40 near Troy; 66/40 then skirted the north and west sides of Collinsville on Vandalia Street, Belt Line Road, and Bluff Road and went past Cahokia Mounds into Fairmont City.((Seratt and Ryburn-Lamont, 29; Jerry McClanahan, EZ66 Route 66 Guide for Travelers (4th edition; Lake Arrowhead, California: National Route 66 Federation, 2015), 25.)) This new alignment carried traffic across the Veterans’ Memorial Bridge (later renamed for Martin Luther King Jr.), which had been completed in 1951.((Joe Sonderman and Cheryl Eichar Jett, Route 66 in Illinois (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 122.))

In 1956, the passage of the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act insured that other city centers and Route 66 itself would be bypassed. By the mid-1960s, the four-lane alignment bypassing Edwardsville was numbered both 66/55 from north of Troy, past Collinsville, and through East St. Louis to the Mississippi River. On November 9, 1967, motorists began to cross the river on the new Bernard F. Dickmann Bridge, commonly known as the Poplar Street Bridge.((Sonderman, 119.)) After Interstate 270 was completed from the overpass near Troy to the Chain of Rocks Canal Bridge, the 66 Bypass designation to north St. Louis was eliminated.((“No Kicks…No 66,” Edwardsville Intelligencer April 8, 1965, 1.))

The State of Illinois decommissioned Route 66 in 1977. Portions of the road then fell under the jurisdiction of local, county, and state authorities, eventually resulting in the varied appearance and maintenance of the various sections.((Route 66 Operational Guidelines, prepared by Barton-Aschman Associates, Inc. (Springfield: Illinois Department of Transportation, Revised May 1997), 5.)) By 1985, official decommissioning of the entire eight-state route was complete.

This subsection of a 1970 Illinois highway map shows the route of Route 66 through Madison County seven years before it was decomissioned.

From the Illinois State Highway Maps collection of the Illinois Digital Archives

Early landmark businesses on Route 66 in Madison County in the 1920s included a gasoline station and an automobile dealership, both owned by the Cassens family, in Hamel; the Edwardsville Hotel and a Madison County Oil Company station in Edwardsville; and the Luna Cafe in Mitchell. Notable hospitality businesses established from the 1930s through the 1950s included the Tourist Haven in Hamel; Green Gables tourist court between Hamel and Edwardsville; Cathcart’s Cafe and the Hi-Way Tavern and Cafe in Edwardsville; and the Canal and Chain of Rocks Motels and the Twin Oaks Gas Station and Cafe in Mitchell. Many of these structures no longer stand; however, the Luna Cafe in Mitchell is still operated under the same name, and the Tourist Haven in Hamel remains a popular roadhouse, currently under the name Weezy’s Route 66 Bar and Grill.

Route 66 Today

Today, Illinois Route 66 and its place in popular culture is preserved, protected, and promoted by the Illinois Route 66 Scenic Byway and the Route 66 Association of Illinois, in cooperation with the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT), formerly the Illinois Division of Highways. Nationally, the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program, created by an act of Congress in 1999, and the Road Ahead Partnership, which began with a roundtable organized by the World Monuments Fund in 2013, protect and promote all of Route 66. In 1995, IDOT began placing “Historic Route 66” signs along roads that formerly carried Route 66. IDOT signage is well-placed in Illinois, including Madison County, to guide travelers onto the various sections sorted generally by IDOT as the 1926-1930, 1930-1940, and 1940-1977 alignments.

All but about 13 miles of the original Route 66 in Illinois can still be traveled.((Seratt and Ryburn-Lamont, 42.)) In Madison County, the alignments can be followed via state roads, frontage roads, and city/village surface streets using the IDOT brown signs and many online and print resources.