Leclaire

The historic Leclaire neighborhood, once referred to as Edwardsville’s “suburb to the south,” was founded as a cooperative community in 1890 and remained a separate village until annexed to the city of Edwardsville in 1934. Newspapers and magazines throughout the United States and Europe reported on the Leclaire experiment, particularly during the first 20 years of its existence. In 1979, due to its unique history, the former village was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

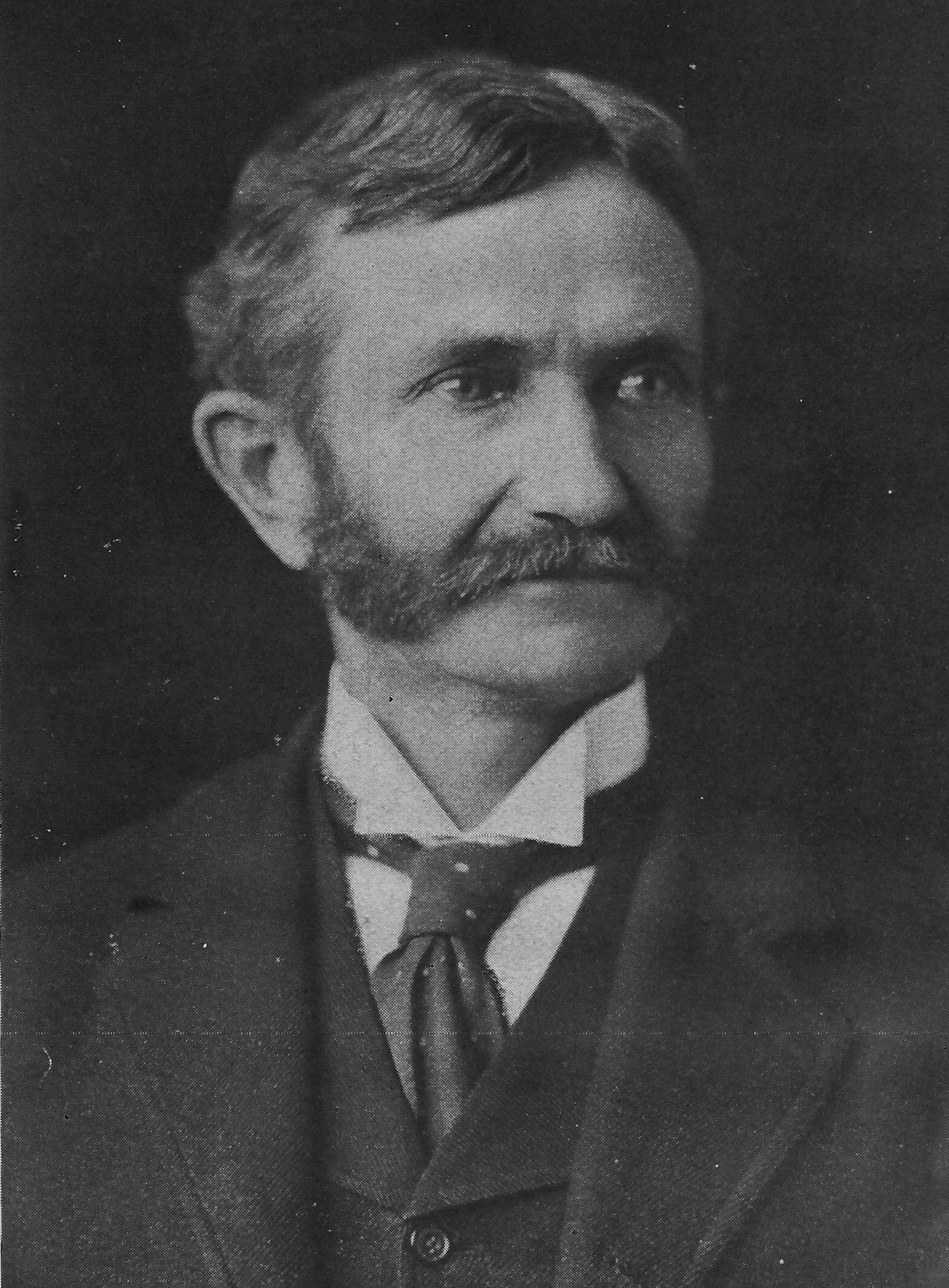

Leclaire was founded by Nelson Oliver Nelson, a St. Louis plumbing manufacturer who, for many years, sought to advance the plight of the working class. Nelson wanted to improve working conditions for his employees and provide housing near the factories so workers and their families could easily participate in recreational and educational programs offered free of charge by the company. Prior to 1890, while still in St. Louis, the N. O. Nelson Company’s manufacturing and distribution businesses began providing profit sharing along with educational and recreational opportunities. The Leclaire cooperative experiment would bring additional benefits.

N. O. Nelson, the industrialist founder of Leclaire

From Friends of Leclaire

When Nelson employees indicated they wanted to relocate to a rural location, company representatives approached leaders of small towns in several Missouri and Illinois communities near their St. Louis headquarters. They were looking for a suitable property to build new factories and a model village. South of Edwardsville they found a 125-acre tract of land with access to water, coal, and transportation. Local businessmen acted quickly to offer a financial incentive. In less than three weeks, the community raised a fund of $20,000 from individual contributions of between $1 and $1,000 to entice Nelson to choose Edwardsville for his enterprise.

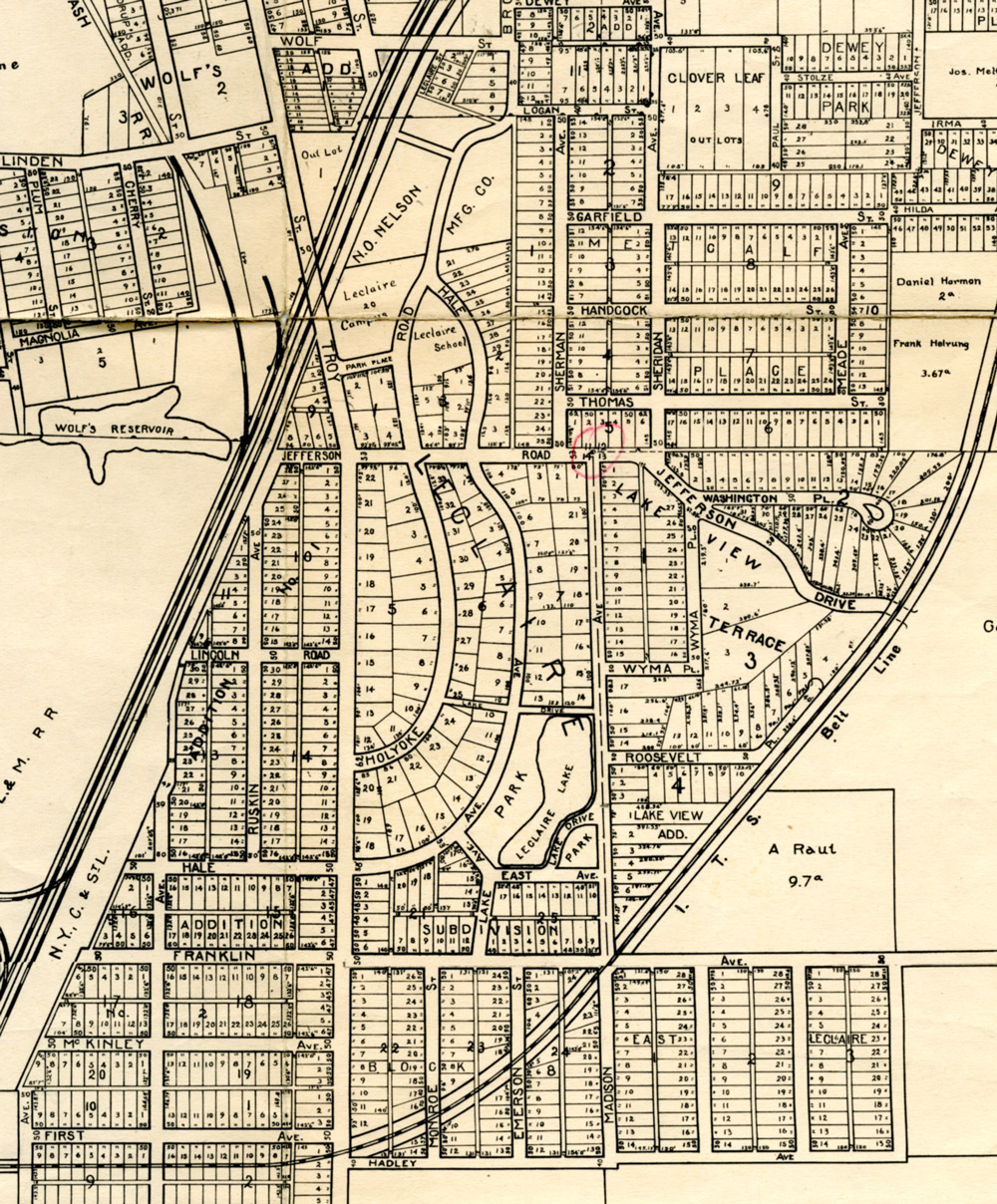

City leaders had hoped to locate property inside the city limits of Edwardsville, but when no suitable site could be found, they were confident that the Nelson investment south of town would soon become a part of Edwardsville. Although Nelson fulfilled all the contingencies for construction and job creation in his contract, it would be 44 years before annexation to Edwardsville. Leclaire, bounded by Madison/Brown Avenues to the east, the railroad tracks to the west, Hadley/McKinley Avenues on the south and Wolf Street to the north, remained an independent village from 1890 to 1934. During that time it earned a reputation for innovations in business, education and residential planning.

The village of Leclaire on a 1931 map of Edwardsville

Courtesy of Paul Jenkins

Nelson’s decision to build a village was not made on a whim. By the late 1880s he was an international leader in the fields of cooperation and profit-sharing, exchanging social theories with others around the world while expanding his St. Louis business. He named his experimental village after the Parisian profit-sharer, Edme Jean Leclaire, but he visited many other social visionaries who provided information and inspiration. Compiling the best ideas from these examples, Nelson founded Leclaire to, in his words, “give work, promote intelligence, provide recreation, foster beauty, and make homes.” These were all factors he determined necessary for men to lead fulfilling lives. Later writers used these words to formulate Leclaire’s founding principles: Work, Homes, Education, Recreation, and Beauty, but with the additional important principle of Freedom.

Work

Work could be considered the most important of these factors since without the factory jobs in Leclaire, there would be no village. The brick factory buildings were designed by architect E. A. Cameron to provide natural light, ventilation in the summer, and heated floors in the winter. There was a fire suppression system and, although industrial accidents were not eliminated, every effort was made to guarantee the safety of the workers. The ivy-covered brick buildings were surrounded by well-manicured lawns and flower gardens giving the complex a campus-like appearance. In 1894, New York World reporter Nellie Bly called the buildings “the ideal perfection of buildings for man to labor in”.

The manufacturing complex of the N. O. Nelson Manufacturing Company in Leclaire

From Friends of Leclaire

Nelson company policies were designed to protect the financial stability of employees. Workers could earn a share of the profits and have a voice in the company if they chose that option. The profit-sharing plan gave Nelson employees a pride of ownership that resulted in a supportive workforce. There were a few short-lived labor strikes over the years, but for the most part, labor problems were rare. Workers also had reasonable hours and competitive wages. There was a provident fund that provided for pensions and sick leave, as well as widow pensions if a worker died, whether or not the death was related to his employment.

Company headquarters for the N. O. Nelson Company (NONCO) remained in St. Louis, but all of the N. O. Nelson Manufacturing Company was moved to Leclaire. The manufacturing company was divided into shops that made a variety of products. In 1900, the shops became independent companies for tax purposes, but all were still owned by the N. O. Nelson Manufacturing Company. The shops included the Cabinet Mill where wood products from cabinetry to millwork were produced. The skilled craftsmen that worked here also fulfilled special contracts, including teller cages for a local bank and an altar still in use at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Edwardsville. The Marble Shop specialized in architectural marble that was cut and installed by Nelson crews in homes, businesses, and even state capitols throughout the Midwest. The Machine Shop, which became Bignall and Keeler, made pipe fitting machines, pumps, gauges, and various mechanical tools expected in the plumbing trade. They also branched out to manufacture specialty items like the Leclaire Bicycle in the mid-1890s. The Brass Shop included a foundry where various plumbing pipes and tools were manufactured. These examples represent just some of the work done in the Leclaire factories. The company’s logo was a stylized “NONCO” that can still be seen on plumbing fixtures and some fire hydrants in Edwardsville today.

Homes

Before homes could be built, housing was needed for workers who were completing the factory buildings as well as building homes. To meet those needs, the company built the “Club House,” a large building that served many purposes. In addition to lodging, it was the community’s first educational building, and it contained a well-stocked library.

Construction of the residential portion of Leclaire began immediately after the village was founded in June of 1890. Julius Pitzman, the innovative landscape architect who laid out the first lots in Leclaire, set them up with a number of protective covenants. The covenants provided for wide, curvilinear streets, large lots, and a deed restriction that limited the properties to residential or educational purposes only. The company paved the streets, provided electric street lights, installed sidewalks, and planted hundreds of trees along the streets of Leclaire. Later sections of Leclaire were laid out with a conventional grid design and smaller lots, but still included the deed restrictions.

Initially the homes were built by the company and then sold at near cost to Nelson employees to encourage home ownership. If a worker became ill and could not make his mortgage, payments were suspended until after he returned to work. The homes were offered in a variety of house designs and the company advertised that no two dwellings were alike. The earliest homes were primarily Victorian cottages that came with electricity and running water. These were followed by bungalows, foursquares, and even some kit homes. Residents could purchase a company-built home or buy an empty lot and build a house themselves, provided the architectural design met company standards.

In later years, lots were sold to investors, usually Edwardsville residents, and many homes in the 1920s were built by local contractors who then sold them to area residents.

Education

Nelson believed in education for everyone, including the working class. Educational programming began with a kindergarten at the Club House in 1892 and continued in the new educational building at 722 Holyoake Road. Commonly called the “School House,” this building provided a large hall for meetings and programs, but had moveable partitions to divide it into classroom space during the day. In the evenings, there were dances, meetings, or programs of the Leclaire Self-Culture Club which featured weekly lectures by Washington University professors or nationally known speakers who, like N. O. Nelson, were part of the social betterment movement at the turn of the century. These included Jane Addams, Edward Everett Hale, Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones, and author Charlotte Perkins Gilman, among others.

In the ten years following the 1895 construction of the education building, there were a series of educational experiments including an industrial school, college, night school, and an academy. The earliest and longest-lived endeavor was the morning kindergarten, founded in 1892, that used the Fröbel Model. This two-year program was free to everyone, including Edwardsville children, until 1931 when for financial reasons the company began charging tuition to students who were not the children of employees. Nelson Manufacturing operated a kindergarten until 1934 when the building was turned over to the Edwardsville School District for a nominal fee.

Recreation

Recreation was an important feature of Leclaire. The company provided sports facilities for baseball, tennis, and later, football. A bowling and billiard hall was constructed and there was a lake for boating, swimming, fishing, or ice skating in winter. Leclaire Park was furnished with boathouses, male & female bath houses, and a large pavilion. Residents organized dances, hayrides, spelling bees, and other activities, and the company sponsored a band that played regularly at entertainments in the village or in Edwardsville. Like the educational functions at the Club House and School House, the recreational facilities at Leclaire were open to all and were often a destination for Edwardsville and even St. Louis visitors.

Beauty

The last of the factors Nelson deemed important for a satisfying life concerned the environment. Nelson knew about the importance of healthy living. He valued the beauty and cleanliness that could be found in the country, and encouraged all in Leclaire to beautify their property by planting gardens and orchards. Nelson himself led by example, so a company greenhouse provided free flowers and competitions were held for the most beautiful yards. Leclaire was laid out so that the entire village had a park-like setting still evident today.

Freedom

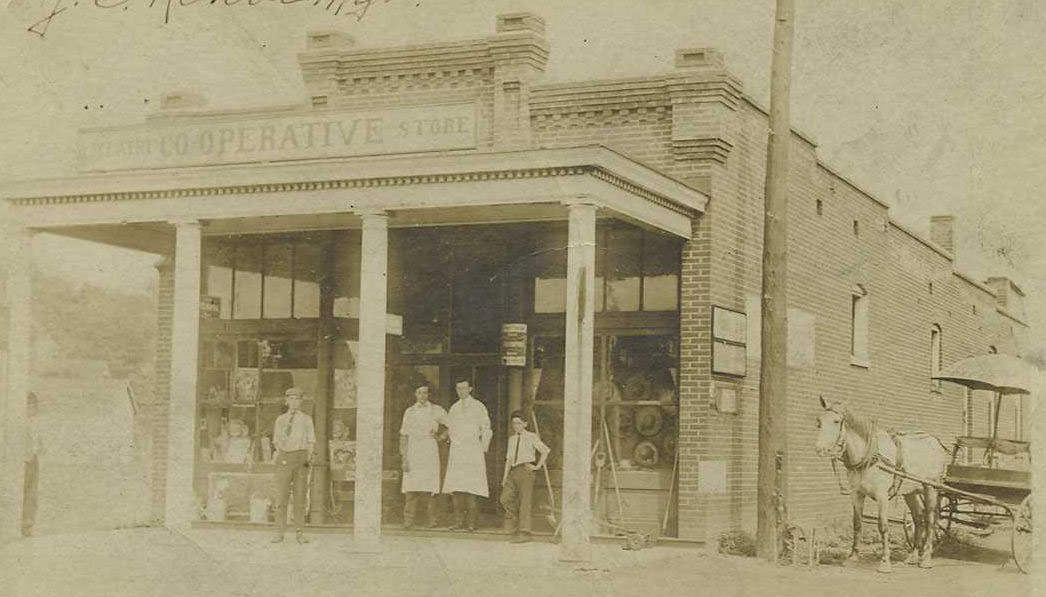

Nelson listed five founding principles for Leclaire, but modern writers add a sixth: Freedom. All of the programs offered by the company were available to employees as well as local residents, but none were mandatory. The freedom to choose whether or not to participate in company programs was entirely up to the individual. Residents of Leclaire could work for Nelson Manufacturing or elsewhere, and workers were under no obligation to live in Leclaire. Participation in recreational and educational programs was also optional. There was also a company store where employees could shop, but unlike other company towns, no one was in debt to the company store. The Leclaire Store was a cooperative where members were charged fair market prices, but were then paid quarterly dividends.

A Different Company Town

All of these benefits made Leclaire unique from other company towns. But there were also individual instances where the company showed compassion and care for the employees. The company closed the factories and hired excursion trains to take workers and their families to St. Louis for a day at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. When money was tight, Nelson would occasionally place extra cash in each pay envelope to make life easier for workers, and if he instituted a program the men did not agree with, they talked it out and, as often as not, Nelson would reverse himself.

Born in Lillesand, Norway, in 1841, N. O. Nelson was a complicated man. He was a capitalist who believed in free enterprise, but also a socialist, a follower of the “Golden Rule”, and a patriot who served for the Union in the Civil War. By 1900, he was a multimillionaire, but by the time of his death in 1922, he had given it all away for the betterment of the working class.

Although Leclaire was not Nelson’s only social experiment, it is considered his most successful endeavor. Other major efforts for social betterment included a chain of co-operative grocery stores in New Orleans, a kindergarten for the children of black employees in his Bessemer, Alabama, factories, and a home for consumptives in Indio, California.

Nelson’s Village of Leclaire was renowned internationally as a noteworthy and successful experiment. It was described in the New York World on numerous occasions but in particular by reporter Nellie Bly in 1894 who wrote at length about the model town where “The labor question is solved and everybody happy in a little village near St. Louis.” The Los Angeles Times also regularly reported on N. O. Nelson, as did the Chicago Daily Tribune and numerous other publications.

In a speech at Leclaire’s 15th anniversary celebration in 1915, Nelson said, “Leclaire extends to you a wide open hospitality, and bids you enjoy today the ease and comfort and beauty and inspiration which we enjoy every day.” More than a century has passed since that day, but the invitation still stands. Residents and researchers are invited to learn about Leclaire’s history and consider the lessons that might be learned for the betterment of future generations.

One of the former buildings of the manufacturing complex in 2019, which now serves as the N. O. Nelson Campus of Lewis and Clark Community College

Photo by Ben Ostermeier

Friends of Leclaire, organized in 1990 following Leclaire’s Centennial celebration, promotes the history of Leclaire through a website (historic-leclaire.org), publications, and a festival, Leclaire Parkfest, held annually on the third Sunday in October.