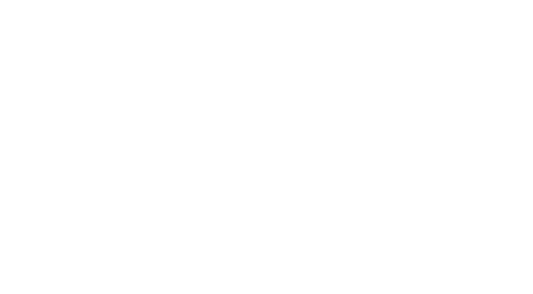

Stephenson, Benjamin (1769 – 1822)

Benjamin Stephenson (1769-1822) was a prominent citizen of frontier Illinois and Edwardsville. During his career he served as sheriff of Randolph County, Illinois territorial representative to Congress during the War of 1812, and Receiver of Public Money in the Federal Land District Office in Edwardsville. He also opened a General Store in Edwardsville.

Portrait of Benjamin Stephenson

From RoxAnn Raisner

Benjamin Stephenson was a child of the American Revolution. He celebrated his eighth birthday only four days after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Two years later the British occupied Philadelphia, and the Continental Congress fled to the town of York, only a few miles from Stephenson’s home in Pennsylvania.

Benjamin was born July 8, 1769 in York County, Pennsylvania to James and Mary Reed and was the youngest boy of seven children. Around 1790, the Stephenson family moved to Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), where he would meet and marry Lucy Swearingen by April 1799. Lucy was 10, and he was 30. The young couple moved to Harper’s Ferry, Virginia where their first daughter, Julia, was born in 1803. Later that same year, the family moved to Russellville, Kentucky. During an 1806 visit to Virginia, their first son, James, was born.

Life in Kentucky and Association with Ninian Edwards

Little is known about Stephenson’s career in Kentucky. The family lived in Kentucky for about six years. Benjamin and Lucy lived in Logan County and Benjamin became one of the original members of the Russellville Lodge of the Free and Accepted Masons.

While living near Russellville in 1809, their second daughter, Elvira, was born. It was probably during this period that Benjamin and Ninian Edwards became close friends and political allies. The alliance was cemented by both politics and by family.

In 1809 President James Madison appointed Ninian Edwards as the governor of the newly founded Illinois Territory; one of governor Ninian’s first acts was to appoint Benjamin as sheriff of Randolph County, Illinois.

Life in Kaskaskia

Between 1809 and 1816 the Stephensons lived in Kaskaskia, capitol of the Illinois Territory. Benjamin V., the last of their four children, was born there in 1812.

Although Stephenson’s duties as sheriff were largely confined to property assessment, the collection of property taxes, and the organization of land sales to settle delinquent taxes, Stephenson still held a position of considerable public significance. Due to unsettled land laws at the time and unsettled claims of French residents in the area, many large parcels of land were sold through this process. Also, because of his official position, Stephenson was closely connected to Governor Ninian Edwards, Territorial Secretary Nathanial Pope, and the three judges of the Territorial Court. Initially, there was no Territorial Legislature and all laws were written, approved, and enforced by the governor and the three judges. Consequently, Stephenson worked daily with the five most powerful people in the Illinois Territory.

Congress

In October of 1814, Shadrack Bond, Illinois’ territorial representative to the 13th U.S. Congress, resigned his position to become the Receiver of Public Money at the Federal Land Office in Kaskaskia. Governor Edwards appointed Benjamin Stephenson to complete Bond’s term. Stephenson was already elected to succeed Bond in the 14th Congress scheduled to convene in 1815. Under normal circumstances, Stephenson would not have served in the 13th Congress because both sessions of the 13th Congress had already adjourned. However, because of the War of 1812 a third session of the 13th Congress was called, and Stephenson took his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives on November 14, 1814. Stephenson arrived in Washington only two and a half months after it was burned by the British.

Stephenson’s initial focus in the House of Representatives was the defense of the frontier from Native American attacks. He and Rufus Easton, the territorial representative from Missouri, actively lobbied for more federal troops on the frontier. They wrote a joint letter to President Madison laying out the problems on the frontier and met with the president on several occasions. A second major concern was the issue of militia pay. Largely because of Stephenson’s work, the War Department finally paid Illinois militia. Stephenson himself collected the money from the War Department and personally brought the money back to Illinois.

By the time Stephenson’s elected term in the House began in 1815, the War of 1812 was over. With the removal of British influence among the Indians on the frontier, the threat of Indian attack was so reduced that Stephenson’s focus changed from the defense of the frontier to numerous social issues. Even though a territorial representative had no vote in Congress, and thus had little power, Stephenson compiled an impressive record of legislative success. Among his accomplishments was a legislative act, which gave the vote to all white males who had resided in the Illinois territory for a year. Under the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance that established the Northwest Territory, only Freeholders (those who owned at least 50 acres of land) could vote. Stephenson argued that most of those who had served in the militia during the war of 1812 were not land owners. Nevertheless, they had defended the territory as members of the militia and, therefore, deserved the vote. The Congress changed the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance to allow voting by non-Freeholders.

Stephenson was also instrumental in the establishment of the Circuit Court system. The original Northwest Ordinance established a three-judge court for the territory. The judges in Illinois believed that they could meet wherever they wanted and, since they lived in Kaskaskia, they only met at Kaskaskia. A citizen living anywhere in the territory with court business had to travel to Kaskaskia and that might take many days. The Illinois Legislature and the governor wanted to change the system so that the judges would go to the people rather than the other way around. The judges argued that the Northwest Ordinance was a federal law and the territorial legislature and governor could not pass any law which superseded federal law. Stephenson convinced the U.S. Congress to pass an act that sided with the legislature and the governor rather than the three judges; thus, judges were required to hold court in each county in the territory. Finally, Stephenson shepherded through Congress numerous changes in the laws governing the sale of public land. He also clarified the boundaries of the territory. For example, the line between Illinois and Missouri was declared to be the middle of the Mississippi River and that islands in the river would be allocated to either territory by their location with regard to this line.

In a long letter to the editor of the Western Intelligencer in the June 19th, 1816, edition of the paper, Stephenson laid out his legislative successes and announced that he would not seek re-election. In the introduction to Stephenson’s letter, Daniel Cook commented on Stephenson’s success in Congress. Cook said, “He made no parade of extravagant promises, but he has shown emphatically his faith by his works.” In other words, Stephenson was a politician who promised little but produced much.

Merchant and Receiver of Public Money

Stephenson returned to Kaskaskia from Congress in May 1816. In June his appointment as Receiver of Public Money in the new Federal Land District Office in Edwardsville was announced. He and his family moved to Edwardsville shortly after the appointment. At the same time, Stephenson opened a general store in Edwardsville. Ads for the Edwardsville store began to appear in the Kaskaskia newspaper in November 1816. These ads ran in issues of the Western Intelligencer for a full year. The newspaper ads said that Benjamin Stephenson was opening a new store in Edwardsville featuring merchandise recently imported from Philadelphia and Baltimore. In November 1817 a new ad started to appear and continued until April 1818, when the last ad for the store appeared.

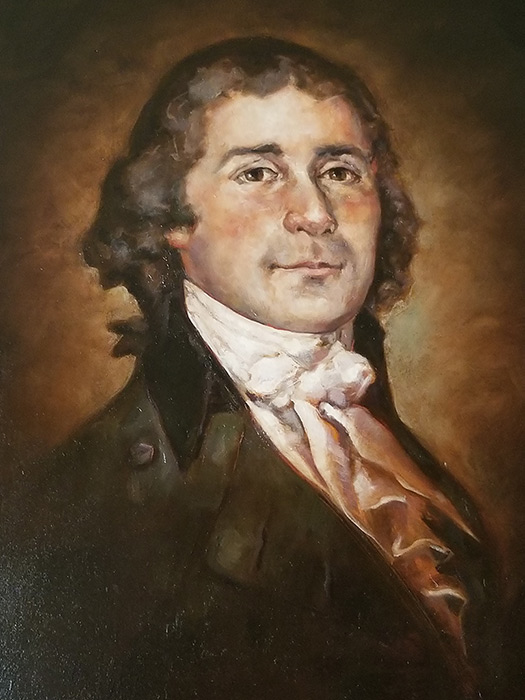

The Stephenson House in Edwardsville in the 21st century

From RoxAnn Raisner

While the store was one aspect of his life, the job as Receiver of Public Moneys for the Edwardsville Land District was without question his principal job. Stephenson served as Receiver of Public Moneys from late 1816 until his death in October 1822. In that time the land office sold 3446 parcels of land valued at $832,699.94. A total of 426,701 acres of land was sold in the Edwardsville office during Stephenson’s tenure. The land offices were enormously important to the federal government and the local economies of the territories. At the end of the American Revolution, the government was deeply in debt and had few sources of income. The one thing the government had in great abundance was land; consequently, the government began to sell the public lands in Ohio and westward. The first office in Illinois opened in Kaskaskia in 1804 and the second opened in Shawneetown in 1812. Due to the tangled land claims cases in the old French district around Kaskaskia, no land was sold at the Kaskaskia office until 1814, ten years after its establishment. The Edwardsville office, established in late 1816, soon dwarfed the other offices in the volume of sales. The sale of land had many benefits to Americans. First, new settlers could serve as a buffer against Indian attacks for the more settled east. Second, the displacement of Indians deprived the English of a valued ally. Third, the sale of land provided a source of funds for the government at a time when funding options were limited. Finally, the land offices raised money on the frontier where almost no one had any. The land office in Edwardsville was the largest business in Edwardsville from its inception and remained significant until it closed in the 1850s. Since the land office was the major source of funds in the area and Stephenson controlled the money, he quickly became “The Paymaster of the Frontier.”

The Death of Benjamin Stephenson

Benjamin Stephenson died on October 10, 1822. There is little information about his death, but the probate records show that, during the months leading up to his death, the family bought quantities of “Yellow Bark.” Yellow Bark, or “Peruvian Bark,” was the bark of the Cinchona tree and the source of quinine used to treat malaria. Malaria was a significant problem throughout the south and reached even as far north as Illinois; thus, the available evidence points to malaria as the cause of Stephenson’s death. He was only 54 years old.