Abraham Lincoln’s Visits to Madison County

Abraham Lincoln holds a seemingly never-ending fascination for us. A search of the Library of Congress online catalog reveals that there are more books written in English on Lincoln than any other person in either American or World History. There have been articles written on seemingly every aspect of his life. Did Lincoln like dogs? What church did he attend? Did he ever smoke cigarettes?((The literature on Abraham Lincoln is extensive. For an insightful overview, see David Donald, “Getting Right with Lincoln,” in Lincoln Reconsidered: Essays on the Civil War Era, 2nd ed. (New York, 1961) and the more recent David W. Blight, “The Theft of Lincoln in Scholarship, Politics, and Public Memory,” in Our Lincoln: New Perspectives, ed. Eric Foner (New York, 2008). A dated but still very useful essay is David M. Potter, “The Lincoln Theme and American National Historiography,” in The South and the Sectional Conflict (Baton Rouge, 1968).)) It is only natural, therefore, that we should be curious about Lincoln’s journeys through Madison County. When was he here? What did he do? Was there anything in his actions that would indicate his future greatness?

Even though Madison County is relatively close to Lincoln’s home in Springfield, Lincoln did not have many reasons to travel to the county. Madison County was not part of the 6th Judicial Circuit in which he practiced law, and his early political career focused on the Congressional and Legislative districts around Sangamon and Morgan Counties. Lincoln did correspond with a number of Madison County residents on legal and political matters, but historians have documented only three occasions when he came to Madison County; once in 1842 and twice in 1858. Each visit was unique and each visit has its own lore and legend.

The Lincoln-Shields Duel, 1842

Abraham Lincoln’s first visit to Madison County came on the morning of September 22, 1842. Lincoln climbed into a boat along the Alton levee along with Dr. Elias H. Merryman, William Butler, and Albert Taylor Bledsoe. They rowed across the Mississippi River to Missouri, a state where dueling, although not legal, was not illegal. Along the muddy shores that morning, Lincoln and his seconds met James Shields and his second, General John D. Whiteside, to settle a matter of honor.((John D. Whiteside was the younger brother of William B. Whiteside whose obelisk grave stands prominently above Bluff Road on the SIUE campus. John D. Whiteside commanded a brigade in the Black Hawk War, served in the Illinois Legislature, and was State Treasurer. The Whitesides were ardent Jacksonian Democrats. They were rough, not formally educated, and very anti-American Indian. Lincoln served under Samuel Whiteside in the Black Hawk War, a cousin of John and William. See Ben Ostermeier, “Whiteside, William Bolin (1777-1833),”. Accessed February 11, 2018 and John Reynolds, Pioneer History of Illinois (1852).)) Looking back upon the incident years later, an embarrassed and wiser Lincoln purported to have said to an acquaintance, “I do not deny it, but if you desire my friendship, you will never mention it again.”((David Donald, Lincoln (New York, 1995), p. 93.))

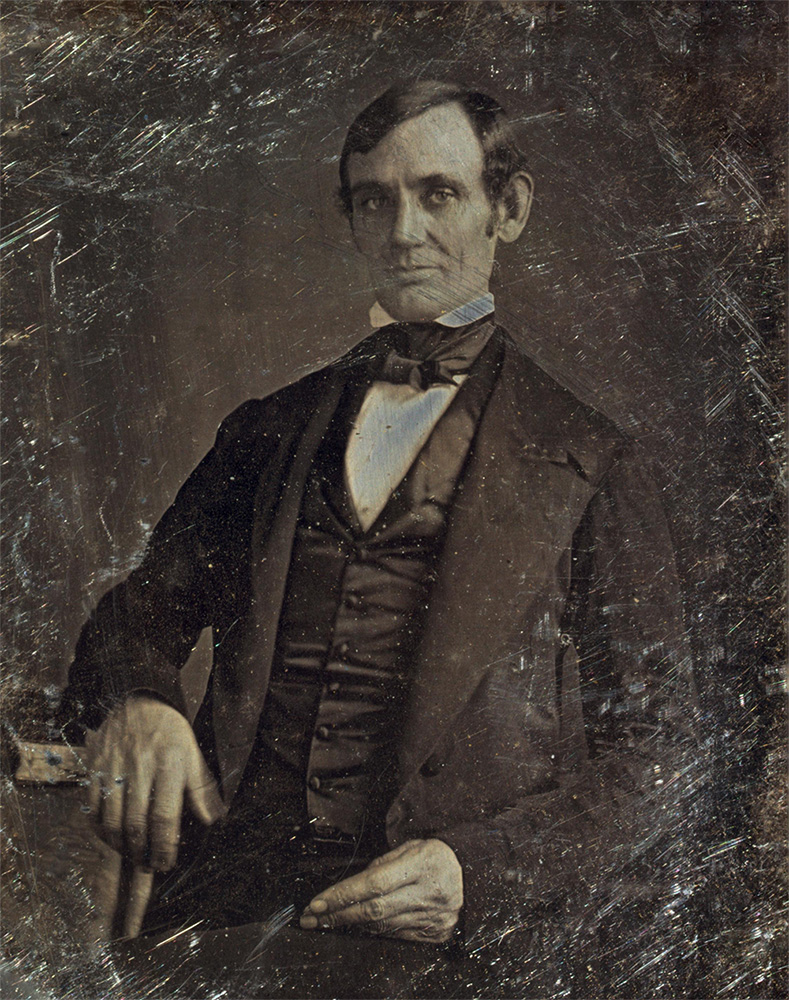

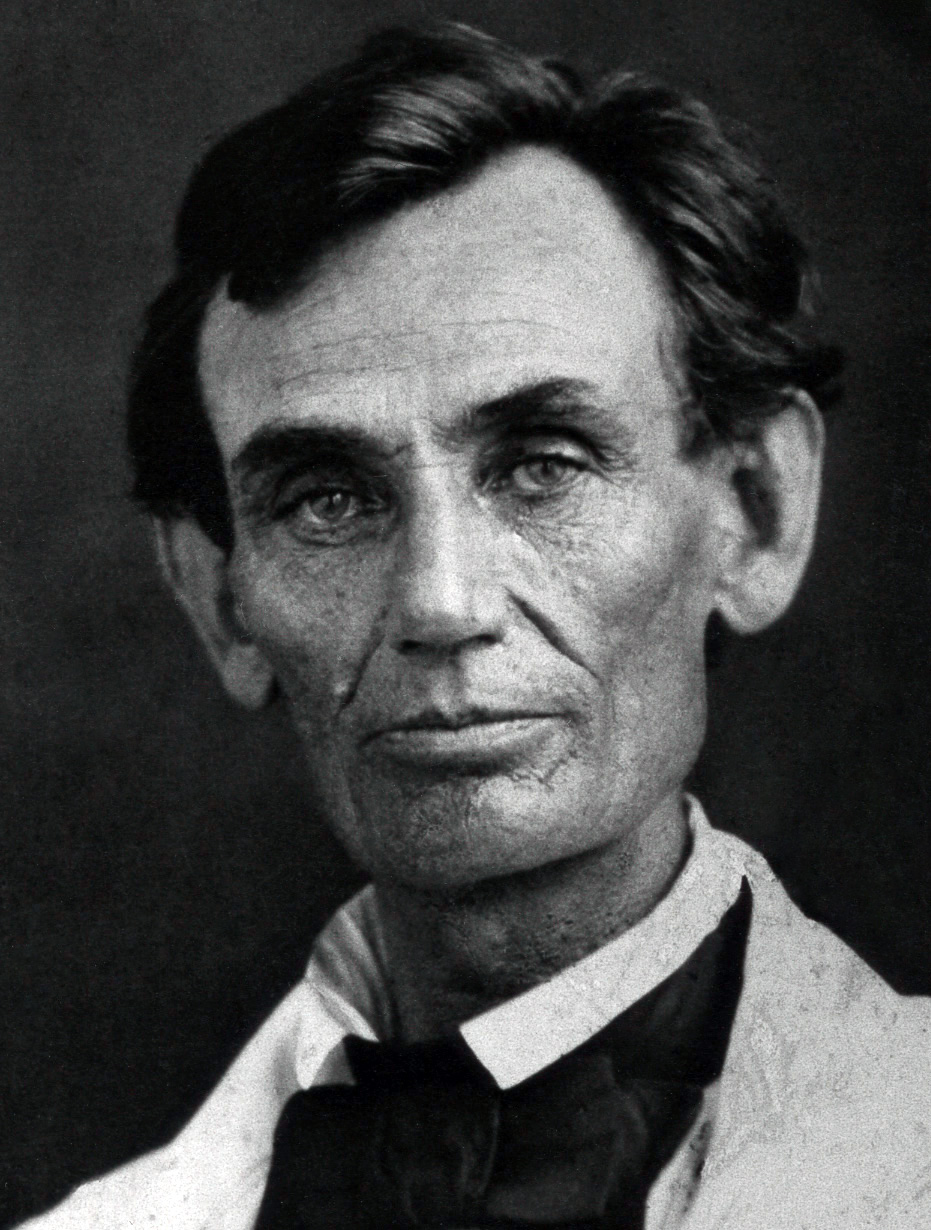

This daguerreotype of Abraham Lincoln was taken in either 1846 or 1847, the earliest known photograph of Lincoln. This was taken a few years after Lincoln’s duel with Shields.

From Wikimedia commons

Like many arguments, the dispute between the young Whig Party lawyer, Abraham Lincoln, and the up-and-coming Democratic Party politician, James Shields, began innocently enough.((James Shields emigrated from Ireland to the United States in 1822. He fought in the Second Seminole War, lived in Quebec, and settled in Kaskaskia where he read law. He was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1836 and then State Auditor in 1839. Interestingly, Shields was not yet a U.S. citizen when he was elected to office. He was appointed to the Illinois Supreme Court in 1843 and fought in the Mexican War from 1846 to 1848, where he was wounded twice and eventually promoted to Major General. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1848 but lost re-election to Lyman Trumbull of Alton in 1854. He moved to Minnesota and was elected as its U.S. Senator in 1858. During the Civil War, he served as General in the Army of the Potomac, notably losing a battle to Stonewall Jackson in 1862. After the war, Shields moved to Missouri where he was again elected to the U.S. Senate. He is the only person to have been elected to the Senate from three different States. Shields died in 1879 in Iowa. See Stephen L. Hansen, “James Shields, 1806-1879” in American National Biography ed. John A. Garraty (New York, 1999).)) Early in 1842, the State Bank of Illinois closed, the result of a crushing state debt caused by reckless spending on internal improvements and by irresponsible banking practices. By August, Governor Thomas Carlin, a Democrat, ordered the State Auditor, James Shields, to inform county tax collectors not to accept the paper notes from the State of Illinois Bank. Flooded with now worthless paper currency, the Illinois economy collapsed.((Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln (New York, 2009), p. 112.))

The Whig Party politically pounced to take advantage of the situation. Whig politicians focused their attacks on Auditor James Shields, a young, ambitious, and prominent Democrat, a man obviously marked for higher office. Young and ambitious himself, Abraham Lincoln took an active role in the Whig assault. Approaching Simeon Francis, the editor of the Sangamo Journal, Lincoln proposed to write a satirical letter under the pseudonym of “Rebecca,” a country woman who lived in “Lost Township.” There had been previous letters from “Rebecca” to the newspaper written by others, but now, Lincoln, using local idioms and mimicking dialect, attacked Shields in what Lincoln thought was a humorous manner. Other Whig Party supporters decided to join in the fun. Notably Mary Todd and Julia Jayne wrote another “Rebecca” letter poking fun at Shield’s reputation with the ladies.((“The ‘Rebecca’ Letter” Sangamo Journal September 2, 1842.))

Shields, however, found nothing funny about the letters. Infuriated, he demanded that Francis tell him the name of the author. Francis revealed to Shields that the author of the “Rebecca” letters was Lincoln. Many biographers claim that Lincoln authorized Francis to tell Shields that it was him in order to protect the reputations of Mary Todd and Julia Jayne. Regardless, upon learning from Francis that Lincoln was the author, an enraged Shield demanded satisfaction on a “field of honor.” Selecting John D. Whiteside as his second, Shields rode to Tremont in Tazewell County where Lincoln was in court. Whiteside immediately presented Lincoln with Shield’s demand for a retraction and an apology. Lincoln later said that Shields’ note was so offensive that he would not respond.((The letters exchanged by Lincoln and Shields and their seconds are included in William H. Herndon and Jesse W, Weik, Herndon’s Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life, 3 vols. (Chicago, 1890, 2:243-259. Also see, Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, (New York, 1952), p. 83 and Abraham Lincoln to Elias H. Merryman, September 19, 1842, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.))

Lincoln returned to Springfield after court, and if he had any hopes that he could avoid the entire situation, they quickly evaporated. The town was abuzz with excitement and rumor over the demand from Shields. Lincoln, consequently, instructed his colleague Dr. Elias H. Merryman to negotiate with Shields. If Shields would submit a more temperate demand, Lincoln said, he would apologize, otherwise he would have no choice other than to accept Shields’ challenge. The negotiations failed and Merryman arranged with Whiteside for Shields and Lincoln to duel in Missouri on September 22.((Thomas, Lincoln, p. 83.))

As the person challenged, Lincoln had the prerogative of selecting the weapons. Knowing that Shields enjoyed a reputation as an outstanding marksman with pistols and with muskets, Lincoln chose broadswords. To make matters even more disadvantageous for Shields, Lincoln insisted that a board be placed on the ground across which they would fight and from which no man could retreat more than eight feet. Clearly, given his height and long arms, Lincoln had the overwhelming advantage.

It is difficult to know what Lincoln was thinking. Obviously, he was serious in proposing the terms of the duel, but was he hoping that Shields, at a distinct disadvantage, would retract his challenge? Lincoln knew that Shields was no coward, but perhaps by choosing broadswords Lincoln was trying to show Shields the absurdity of fighting a duel.

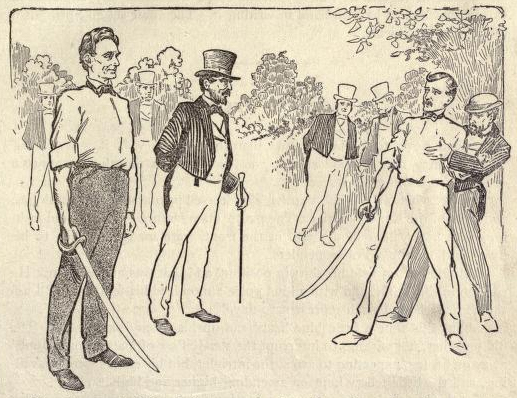

This fanciful drawing of the Lincoln-Shields duel was drawn more than half a century later, in 1901.

From Alexander K. McClure, “Abe” Lincoln’s Yarns and Stories (Chicago: Henry Neil, 1901), 67.

Exactly what happened next is uncertain. According to Lincoln lore, the seconds resumed negotiations after Lincoln stretched to his full height and casually whacked off a tree branch with his broadsword. The end result was that a bargain was reached. Lincoln disavowed any intention of injuring Shields’ personal character, Shields subsequently withdrew his challenge, and the men shook hands and returned to Illinois, reputations intact.((White, A. Lincoln, p. 115. Some books and articles incorrectly suggest that the infamous “Bloody Island” was the location of the Lincoln-Shields non-duel. Bloody Island was a sandbar that grew into an island about one mile in length and 500 yards wide. Maps show the island directly across from St. Louis. Because it was between Missouri and Illinois with uncertain jurisdiction, it became the site of a number of famous duels. Thomas Hart Benton, the future United States Senator from Missouri and close friend of Andrew Jackson, fought two duels against the same man on the island, killing his opponent in 1817. There were a number of other duels fought on the island by prominent public figures.

The island continued growing and threatened to block the St. Louis levee. The Army Corps of Engineers, under Colonel Robert E. Lee, build a series of dikes in 1838 that forced the main channel of the river to flow on the western side of island. The result was that the island soon disappeared, becoming part of the Illinois shore, four years before the Shields-Lincoln duel. A.W. Moore, “History of Bloody Island and its Duels,” Documents from the Illinois State Historical Library Manuscripts Collection, Accessed February 11, 2018; “The Age of Political Duels,” in Missouri State Archives: Crack of the Pistol: Dueling in 19th Century Missouri, Missouri Digital Heritage, Accessed February 11, 2108.))

It is interesting to note, however, the entire affair produced such rancor that Shields challenged one of Lincoln’s seconds, William Butler, to a duel with muskets at 100 yards. This duel also failed to materialize. In the end, Lincoln never wished to be reminded again of this trip to Madison County.

Lincoln in Edwardsville and in Highland, 1858

Abraham Lincoln’s second trip to Madison County came in September 1858 during the hotly contested senatorial campaign against Stephen A. Douglas. The trip was brief. Lincoln arrived in Alton from Hillsboro on Friday September 10, traveled to Edwardsville on the 11, gave his speech around 1 p.m., and moved on to Highland where he gave another speech that same evening. On Sunday September 12, Lincoln left Madison County and journeyed to Greenville where he delivered a two-hour address the next day. Although his stay in Madison County was short, and his speeches in Edwardsville and Highland were brief, the trip was politically important.

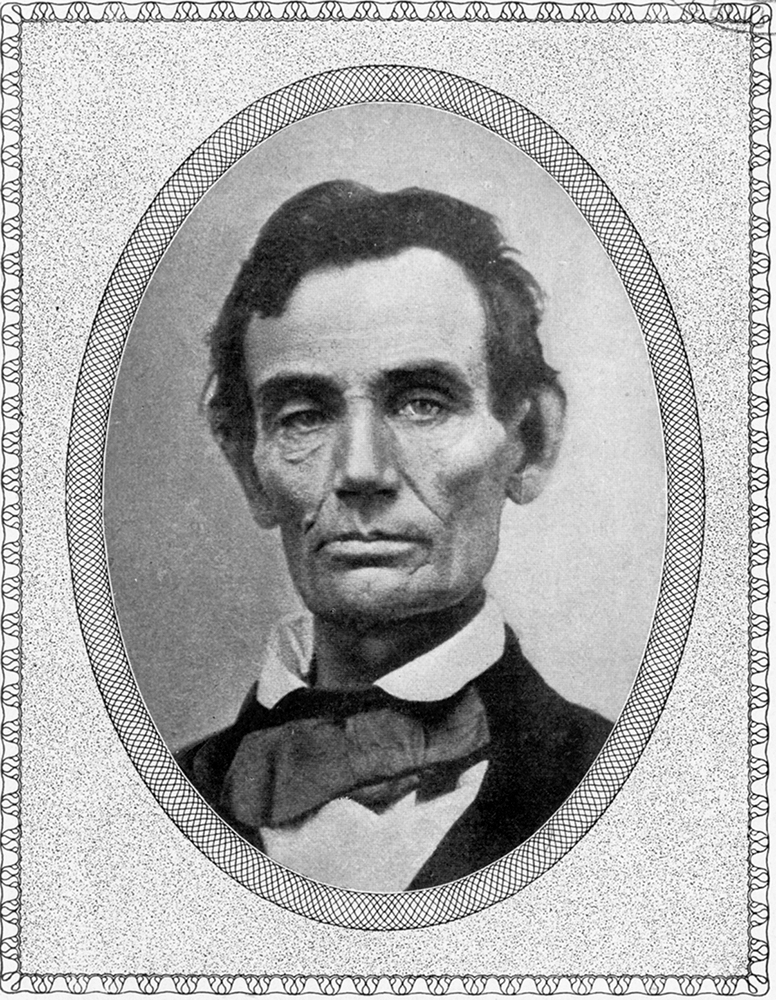

This photograph of Abraham Lincoln was taken August 25, 1858, seventeen days before his visit to Edwardsville and Highland.

From Wikimedia commons

The 1858 political map in Illinois was complicated. In the presidential contest two years earlier, Democrat James Buchanan garnered 34.4% of the vote in Madison County, while Republican presidential candidate James Fremont carried 26.3% of the vote. Significantly, Madison County was won by the American Party, or the Know Nothings. Led by former President Millard Fillmore, the Know Nothings won Madison County with 39.3% of the vote.((The Know Nothings made their first appearance in Illinois politics early in 1855. Initially, they were a secret fraternal organization that began in the 1840s and flourished in the 1850s. Originally named the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, they earned their name as Know Nothings because when asked about the Order, they responded by saying “I know nothing.” The Know Nothings were ardently anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. As the number of immigrants rapidly increased, the Know Nothings became more political. In Illinois alone, the number of German immigrants increased nearly five-fold, the number of Irish quadrupled, and the number of immigrants from England doubled. The nativists felt that the American way of life was being threatened and overwhelmed by the tide of mostly Catholic immigrants. The Know Nothings began organizing themselves into the American Party in 1854, and by 1856, the American Party threatened to replace the defunct Whig Party as the major opposition to the Democratic Party. The Know Nothings, however, soon split over the issue of slavery, and had mostly disappeared as an organized political movement by 1860. See William E. Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 (New York, 1987) and Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850s (New York, 1978). The Know Nothings made their first appearance in Illinois politics early in 1855. Initially, they were a secret fraternal organization that began in the 1840s and flourished in the 1850s. Originally named the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, they earned their name as Know Nothings because when asked about the Order, they responded by saying “I know nothing.” The Know Nothings were ardently anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. As the number of immigrants rapidly increased, the Know Nothings became more political. In Illinois alone, the number of German immigrants increased nearly five-fold, the number of Irish quadrupled, and the number of immigrants from England doubled. The nativists felt that the American way of life was being threatened and overwhelmed by the tide of mostly Catholic immigrants. The Know Nothings began organizing themselves into the American Party in 1854, and by 1856, the American Party threatened to replace the defunct Whig Party as the major opposition to the Democratic Party. The Know Nothings, however, soon split over the issue of slavery, and had mostly disappeared as an organized political movement by 1860. See William E. Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 (New York, 1987) and Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850s (New York, 1978). For Madison County election results in 1856, see Howard W. Allen and Vincent A. Lacey, eds., Illinois Elections, 1818-1990: Candidates and County Returns for President, Governor, Senate, and House of Representatives (Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1992), p. 136.)) By 1858, the American Party was defunct in Illinois and no Know Nothing candidates contested any of the elected offices in Madison County. For Lincoln and Douglas, consequently, winning the votes of these former American Party voters was the key to victory.

Lincoln had reason to be encouraged that he might persuade the Know Nothings to support the Republican candidates to the Illinois General Assembly. First, in 1856, despite losing the county in the presidential contest, a majority of Madison County voters supported the Republican candidate for the U.S. Congress and a plurality supported the Republican candidate for Governor. Second, Lincoln was a personal friend of Joseph A. Gillespie of Edwardsville, a leading figure in the mostly defunct Know Nothing Party and now a Republican Party candidate to the State Senate.((Joseph Gillespie was a prominent attorney and legislator who lived in Edwardsville and in Wood River. Born in New York in 1809, his father moved the family to Edwardsville in 1819. Joseph Gillespie served in the Black Hawk War when he probably met Abraham Lincoln. Gillespie was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1839. In 1840, he was one of Whigs who, along with Lincoln, jumped out of a window to prevent a quorum when the Democrats tried to pass legislation against the Whig-supported State Bank. Gillespie served in the Illinois House and in the State Senate at various times until 1860. He was a Whig and then a Know Nothing before joining the Republican Party in 1856. He was always a strong supporter and close political ally of Lincoln. He died in 1885 and is buried in Oak Lawn Cemetery in Edwardsville. For additional information about Gillespie, see Paul D. Nygard, Judge Joseph Gillespie of Illinois: Whig, Know Nothing, Republican, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville: M.A. Thesis, 1992.)) Third, U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull of Alton was a strong supporter of Lincoln.

Even with these advantages, Lincoln knew that the contest in Madison County would be close. In July, Lincoln wrote to Gillespie calculating the odds: “if they [the Democrats] get one quarter of the Fillmore votes and you three quarters, they will beat you [by] 125 votes. If they get one fifth and you four fifths, you beat them 179. In Madison [County] alone if our friends get 1000 of the Fillmore votes, and their opponents the remainder—658, we win by just two votes.”((Abraham Lincoln to Joseph Gillespie, July 16, 1858. Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress. Also Lincoln to Gillespie, July 25, 1858, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.))

When Lincoln arrived in Edwardsville that clear Saturday morning, he met with local Republican Party officials at the home of Matthew Gillespie, brother of Joseph Gillespie. The men moved on to the Marshall House, formerly known as Haskett’s Tavern, where they ate a noon-time meal. Mary Rollins recalled that as an eleven-year old girl, she had gotten up at midnight to peel potatoes. She said that she had to set two tables running the length of the room, each draped with flags and bunting. Ms. Rollins remembered that she had to clear the tables three times to accommodate the diners. After the meal, Joseph Gillespie arranged for a band and a small parade to escort Lincoln to the Court House for his 1 p.m. speech. One eyewitness reported that the parade was a “poor showing” while another recalled running alongside the small procession yelling racial slurs at Lincoln.((On Lincoln’s visit to Edwardsville, including the eyewitness accounts, see “Abraham Lincoln in Edwardsville,”. Accessed January 9, 2018; Old Wabash Hotel in Historic American Buildings Survey (Historic American Buildings Survey: Bloomington, Illinois, 1934), accessed January 9, 2018.))

Lincoln carefully prepared his speech for what the sympathetic Chicago Tribune described as a respectful “cluster” of citizens.((Chicago Tribune, September 15, 1858.)) Knowing that he needed to appeal to the former Know Nothing voters, Lincoln organized his speech around four questions: what is the difference between the Democratic and the Republican parties? What is the opinion of Henry Clay on whether or not slavery is good for the nation? What does Douglas’s plan of Popular Sovereignty really mean? And lastly, what will happen after the next Dred Scott Decision?((For a transcript of the speech, see Abraham Lincoln, “Speech at Edwardsville, Illinois,” September 11, 1858, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 3 (University of Michigan Digital Library Production Services: Ann Arbor, 2002), accessed April 23, 2018.))

Lincoln argued that the difference between the Democrats and the Republicans was that the Republicans “consider slavery a moral, social and political wrong, while the [Democrats]…do not consider it either a moral, social or political wrong; and the action of each, as respects the growth of the county and the expansion of our population, is squared to meet these views.” He argued that government was instituted to secure the “blessing of freedom, and that slavery is a[n] unqualified evil to the negro, to the white man, to the soil, and to the State.” He then turned his attention to the antislavery positions of Henry Clay, the deceased Whig Senator and presidential candidate from Kentucky. Lincoln paid tribute to Clay and referenced him in the speech because he admired Clay but also because he knew that many of the Know Nothing voters had been Whigs who fiercely supported Clay.

Lincoln then focused on his last two questions in his relatively brief speech. First, using humor, Lincoln attacked Douglas’ idea of Popular Sovereignty as a solution to the issue of slavery in the territories. It meant nothing more, Lincoln argued than to give white people the right to whip slaves in the territories under the self-proclaimed right of self-government. Second, Lincoln concluded his speech by asking what might happen now that the Dred Scott Decision ruled that the federal government could not prohibit slavery in the territories. Lincoln told his audience to prepare for the Supreme Court to rule next that a State could not prohibit slavery anywhere, which meant that slavery could be introduced into Illinois. The Alton Weekly Courier reported that Lincoln’s speech received “loud applause.”((Alton Weekly Courier, September 16, 1858.))

Lincoln did not linger long in Edwardsville. He traveled on to Highland where he gave another talk that evening. Unfortunately, no record remains of what Lincoln said in Highland. Neither any of the newspapers nor Lincoln’s own papers have any notes about his Highland speech. On Sunday, September 12, he left Highland for Greenville, where on the 13, he gave a two-hour talk.

Lincoln In Alton, 1858

Lincoln returned to Madison County for the last time in October 1858 for the seventh and last debate with Stephen Douglas. Even stripped of all the lore and legend, the Lincoln-Douglas Debates were momentous occasions. While debates and stump speaking by political candidates were common in Illinois, this campaign was unprecedented. It was exceptional because politicians did not campaign directly for the U.S. Senate. Senators were chosen by the State Legislature, not by the voters, and campaigning for the U.S. Senate was highly irregular. The campaign was also unusual because of the intensity of partisanship. Newspapers, in particular, viciously attacked each candidate. Another measure of the campaign’s passion was the fact that voter turnout would reach more than 80%. A third factor that made the campaign exceptional was the level of national interest. The Richmond, Virginia Enquirer wrote that the “great battle of the next Presidential election is now being fought in Illinois” while the New York Times wrote that Illinois was “the most interesting political battle-ground in the Union.”((Quoted in Donald, Lincoln, p. 214. An excellent study of the debates is found in Don E. Fehrenbacher, Prelude to Greatness, Lincoln in the 1850s (Stanford, 1962).))

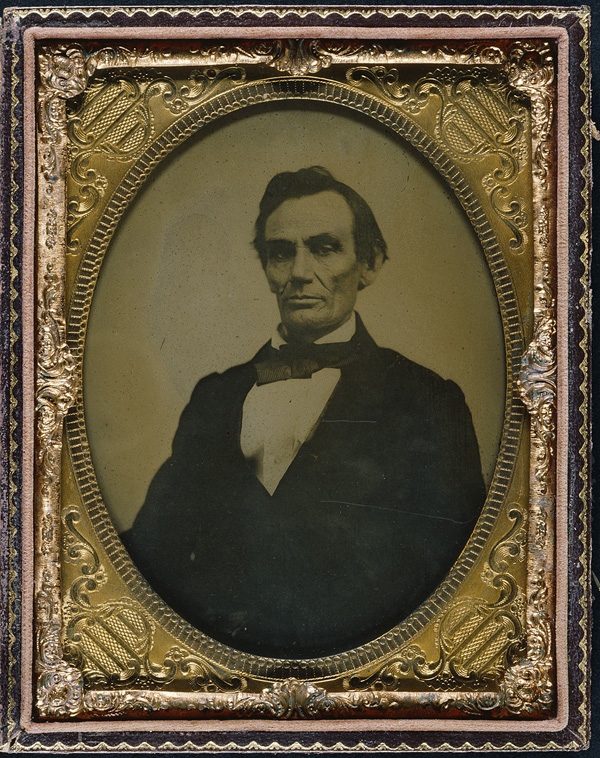

This photograph of Lincoln was taken October 11, 1858, four days before his visit to Alton

From the National Portrait Gallery on Flickr

On October 14, 1858, Lincoln left Quincy, Illinois, the site of the sixth debate, and traveled by steamer, the City of Louisiana, with Stephen Douglas aboard down the Mississippi River. They reached Alton by 5 a.m. on Friday morning October 15. Both men were hoarse and near exhaustion from the strain of campaigning. Lincoln made his way to the Franklin House to rest where he met Mary Todd and their eldest son, Robert, both of whom had arrived by train that same morning from Springfield.

The day was dreary, blustery, and damp. Nevertheless, people began arriving early in the morning. They came by horseback, carriage, and every other imaginable kind of wagon. The steamer Baltimore from St. Louis brought a load of passengers. By about 10:30 in the morning, the train on the Chicago, Alton & St. Louis railroad brought people from “Springfield, Auburn, Girard, Carlinville, Brighton, and Monticello.” The Alton Weekly Courier reported that other trains, one with “eight full cars,” also unloaded passengers from an unknown number of towns. About noon, an extra steamer from St. Louis, the White Cloud, landed at the levee.((Alton Weekly Courier, October 21, 1858.))

Into this hubbub of about 6,000 spectators marched the Springfield Cadets, a military company that paraded through the streets. The company camped by Merritt’s Coronet Band which played music for the milling crowd. Early in the afternoon, a band from Edwardsville arrived to “charm the senses and soothe dull care away.”((Ibid.))

According to the Weekly Courier as people went up and down the streets, some “hurrahed for Lincoln” and others shouted “huzzahs for Douglas.” Crowds of people thronged the stores, choked the street corners, and jostled through the streets. Arguments broke out among passionate supporters. Fists shook but few punches were thrown. All the while, vendors hawked their wares. Saloons filled with people looking for food and drink. With flags flapping in the wind and signs waving, the Weekly Courier pronounced the entire affair a glorious display of democracy.((Ibid.))

By agreement, neither Lincoln nor Douglas organized a parade or demonstration as they made their way to the platform. At 2 o’clock, in front of the new city hall, Lincoln and Douglas began their three-hour debate. The people crowded in to hear. Douglas opened the debate, speaking for an hour. Lincoln followed with a 90-minute rejoinder and Douglas closed the debate with a 30-minute conclusion.

These statues of Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln commemorate the final Lincoln-Douglas Debate held in Alton on October 15, 1858.

Photo by Kevin Sablin from Flickr

In his opening, Douglas used many of the same arguments against Lincoln that he had employed throughout the campaign. Specifically, Douglas said that Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech showed that the Republicans were an extreme party of radicals that opposed the legitimate ruling of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott Case. The “Little Giant” also attacked Lincoln for supporting the equality of the races. He then turned to his own defense. Douglas declared that he was the true moderate between two extremes; the abolitionist Republicans in the North and the fire-eating slave-owners in the South. Douglas said that he was trying to preserve the nation as the Founding Fathers had created it and that he was the defending our freedoms against radicals and extremists.

Lincoln’s response was calculated to show that he and the Republicans, not Douglas, were the conservatives, the defenders of the original intent of the Founding Fathers. Lincoln argued that it was slavery that threatened freedom and democracy and that its advocates had perverted the Constitution and the founding principles of the nation. If left unchecked, he declared, the slave power would eventually take away our freedom, first by making the territories open for slavery and then by making it illegal for any state to prohibit slavery. Lincoln shrugged off the charge of being in favor of racial equality by saying that he had “no purpose…to introduce political and social equality between the white and black races.”((For a transcript of the debate, see Rodney O. Davis and Douglas L. Wilson (eds), The Lincoln-Douglas Debates (Chicago 2008).))

The pro-Republican Chicago Tribune reported that the speakers did not generate more than ordinary applause. Perhaps the lack of enthusiasm reflected the dreary weather, or perhaps the crowd mirrored Lincoln’s and Douglas’ emotional and physical exhaustion. Lincoln left Alton the next day by train. In a few short weeks, he would learn that he had been unsuccessful in persuading enough Madison County voters to support Republican candidates, and that he had failed to win the Senate seat occupied by Stephen A. Douglas.

The voters of Madison County supported Democratic Party candidates by a slim majority in 1858. Democrat Samuel A. Buckmaster defeated Joseph Gillespie by 184 votes for the State Senate. Phillip Fouke, a loyal Douglas supporter, edged out the Republican Joseph Baker by 131 votes in the Congressional race. The table below shows the vote in Madison County in 1858 by precinct as reported by the Alton Weekly Courier.((Alton Weekly Courier, November 11, 1858.))

| Precincts | State Senate Buckmaster (D) |

State Senate Gillespie (R) |

U.S. Congress Fouke (D) |

U.S. Congress Baker (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alton | 597 | 488 | 596 | 485 |

| Upper Alton | 181 | 216 | 177 | 228 |

| Edwardsville | 279 | 251 | 289 | 236 |

| Marine | 117 | 113 | 115 | 114 |

| Omph-ghent | 48 | 97 | 46 | 99 |

| Bethalto | 129 | 65 | 126 | 64 |

| Highland | 110 | 170 | 96 | 186 |

| Six Mile | 119 | 36 | 120 | 34 |

| White Rock | 74 | 45 | 74 | 44 |

| Looking Glass | 60 | 60 | 68 | 57 |

| Monticello | 67 | 119 | 67 | 117 |

| Saline | 30 | 45 | 29 | 46 |

| Alhambra | 41 | 60 | 41 | 60 |

| Troy | 77 | 123 | 78 | 123 |

| Silver Creek | 39 | 27 | 38 | 27 |

| Madison | 115 | 8 | 112 | 7 |

| Collinsville | 147 | 110 | 130 | 129 |

| TOTAL | 2221 | 2037 | 2185 | 2054 |

Note: the numbers do not total. The errors are in the numbers reported for the precincts because the totals correspond to the official county totals. The precinct level errors may have resulted from the newspaper printing or from transcribing. For a map of the boundaries of each precinct, see Campbell, R.A., Topographical & Sectional map of Madison, St. Clair, and Monroe Counties. Chicago: R.A. Campbell, 1870.

Even though Lincoln wasn’t able to convince enough former Know Nothings to support Republican candidates in 1858, a sufficient number of them changed their minds about the Republican Party, or at least about Lincoln, by 1860. Madison County voters gave Lincoln a slim 61 vote plurality over Douglas in the 1860 Presidential election.((In Madison County in the 1860 Presidential election, Lincoln received 3,161 votes, Douglas received 3,100, John Bell received 178, and John C Breckinridge received 21. Allen and Lacey, eds., Illinois Elections, 1818-1990, p. 145. However, some citizens of Madison County soured on Lincoln by the 1864 election, in which George B. McClellan won with 3,287 votes to Lincoln’s 3,156, a margin of 131 votes. Allen and Lacey, eds., Illinois Elections, 1818-1990, p. 155.))

When the train carrying Lincoln steamed out of Alton that October day in 1858, it would be the last time he visited Madison County. His three visits did not predict the greatness that he would achieve in confronting profound challenges, facing unbearable tragedy, and making decisions that affect Americans yet today. Instead, Lincoln’s visits to Madison County stand more as a prelude that reveal the evolution and growth of an ambitious politician who would later become statesman.

Lincoln in 1858, the year he visited Madison County twice

From Wikimedia Commons