Madison County (1812-2012): Reflecting Illinois and National History

I. Madison County Microcosm

Changes in the economic role, political contributions, and environmental landscape of Madison County during 200 years reflect, on a smaller scale, historical experiences of people in the state and the nation. Created in 1812, Madison County housed, by 1816, the busiest Federal Public Land Office on the northwestern frontier. Before the Civil War, the County’s farms continued the earlier French practice of supplying foodstuffs to New Orleans. After the building of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and the coming of railroads, produce and meat from the county flowed into international trade, as the smaller farms of the early 19th century gave way to large acreages, often incorporated, in the 20th and 21st centuries. Massive industrial development after the Civil War was accompanied by thousands of European immigrants who joined regional migrants leaving their farms for Madison County’s river bend towns: Venice, Madison, Granite City, Hartford, South Roxana, Roxana, Wood River, East Alton, and Alton. Even smaller towns of the interior, particularly Highland and the county seat, Edwardsville, housed primary manufacturing concerns making products such as canned milk, ball bearings, beer, clothing, and radiators. The county’s wealth of coal, water, and hardwood forests supported many factories, which contributed importantly to the nation’s efforts in two World Wars. Yet, by the end of the 20th century, Madison County, like the rest of industrial America, suffered from job losses due to changes in the global economy organized by giant companies. County leaders, like those in other parts of Illinois and across the United States, sought to re-invent and re-structure their communities, to create employment, and thus to fit the region into the new world of an economy based on services.

During two centuries, Madison County provided Illinois with significant politicians, including founders of both the territory and the state, as well as four governors. Today, although corporate critics have labeled it a “judicial hellhole,” Madison County’s distinguished lawyers and sympathetic juries have gained large awards for workers damaged by asbestos and tobacco use. With St. Clair County to the south, Madison County has long been the largest concentration of voters in Illinois outside of Chicago and the “collar counties” surrounding that city.

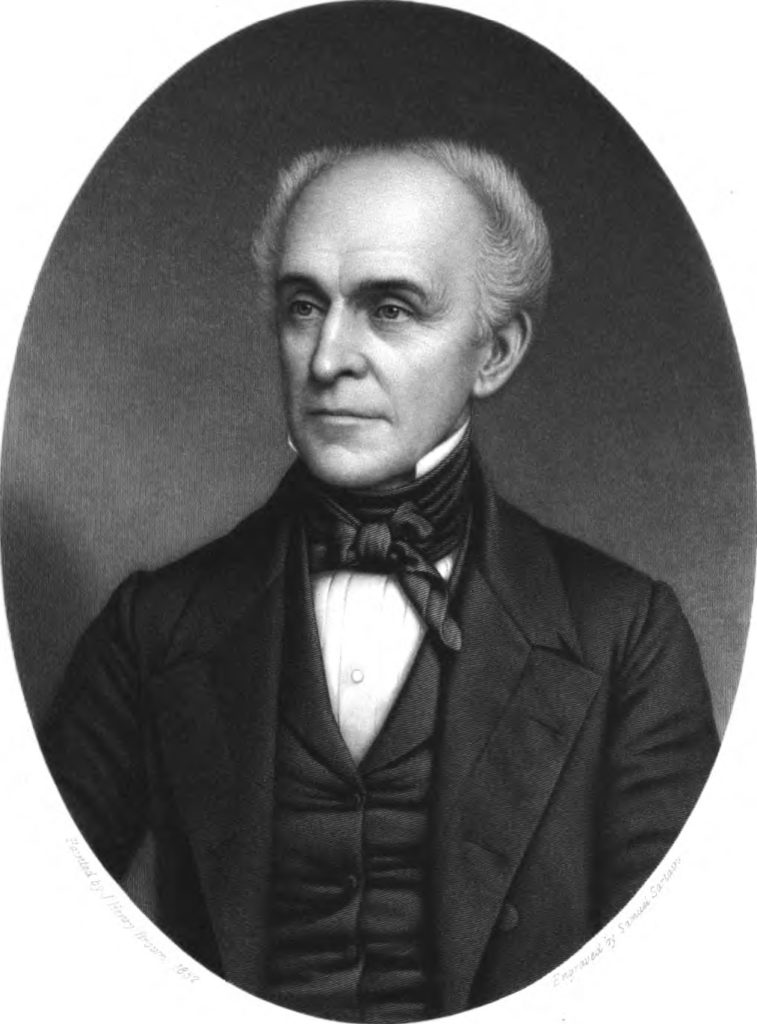

II. Ninian Edwards: Founder

Portrait of Ninian Edwards

From Evarts Boutell Greene and Clarence Walworth Alvord, eds. Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library: Volume IV, Executive Series, Volume I, The Governors’ Letter-Books 1818-1834 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1909), 116.

As Illinois first and only Territorial Governor (1809- 1818), Ninian Edwards was an energetic Maryland-born lawyer, land speculator, and politician who, at the age of 32, had been Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Kentucky. In 1809, when Illinois became a territory separate from Indiana, Edwards and Benjamin Stephenson (1769-1822), also a notable early politician and militia officer during the War of 1812, moved at the same time from Logan County, Kentucky, to Kaskaskia, the Territorial capital. On September 16, 1812, Governor Edwards proclaimed the existence of Illinois Territory’s third county, Madison, named for his presidential patron. (Earlier counties, created before Illinois became a separate Territory, were St. Clair and Randolph, further south along the Mississippi.) Edwardsville, Madison County’s seat, was later named for Edwards by Thomas Kirkpatrick, appointed by the Governor as one of three new Madison County Judges. Kirkpatrick platted Edwardsville after 1813, and his farm, beside Cahokia Creek at the town’s west end, housed the first county court.

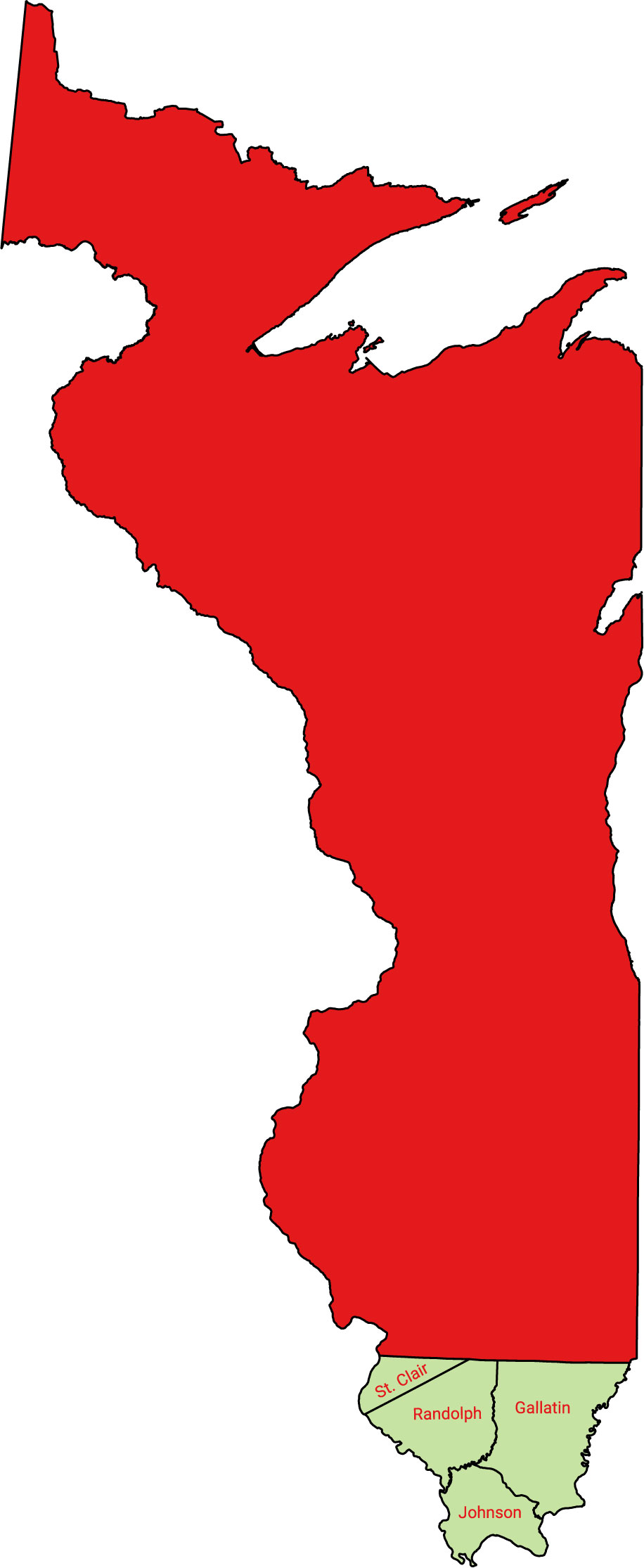

The original Madison County was enormous. The Mississippi River formed the western boundary, while the Wabash River marked the eastern boundary above a line extended from the northern part of St Clair County, which it abutted on the south. To the north, Madison County included The Military Tract, millions of acres granted to veterans of the War of 1812. John Reynolds (1788-1865), who grew up on a farm southeast of Edwardsville, served as a Ranger in the War of 1812, and was later Governor (December 1830-November 1834), remembered in 1861 , perhaps with a twinkle, that the County’s original northern boundary, “I think, reached to the north pole.” More modestly, Ninian Edwards had announced the northern boundary as “Upper Canada.”

The original extent of Madison County in 1812, which extended as far north as the Canadian border. For more on the border changes to Madison County, see Border History of Madison County.

Map by Ben Ostermeier

Madison County’s final borders were established in 1843. All counties with red text have different borders today. The last change to Illinois county borders was in 1859. For more on the border changes to Madison County, see Border History of Madison County.

Map by Ben Ostermeier

III. When the Prairie State had prairies

Vast prairies of Madison County, often named for pioneer families who began forcibly to appropriate these lands from Native Americans after the American Revolution, surely fostered Illinois’ reputation as “the Prairie State.” By 1900, these original grasslands, interspersed with woods of mighty oak, hickory, and walnut understoried by red buds, elderberries, hawthorns, and plums, had been converted to a new landscape of fenced farms, railroads, roads, towns, and cities. Gershom Flagg (1792-1857), the third of 11 children of a sturdy Vermont family, left for Illinois in 1816. He acquired acreage in Ft. Russell Township, east of Alton and north of Edwardsville. In 1817, he wrote to one of his brothers, describing the wonders of the wild prairie and unintentionally predicting its decline. Recalling a recent visit to the Mississippi flood plain, called by locals The American Bottom, which began at Alton and ran along the bluffs forming the western edge of both St. Clair and Madison counties, Flagg noted that “bottom Prairies are covered with … grass about 8 feet high …. The Prairies,” he wrote, “are continuously covered (in the summer season) with wild flowers of all colors which gives them a very handsome appearance ….When the fire gets into the high thick grass it goes faster than a horse can run & burns the Prairie smooth.” (“Prairie” was always capitalized in the writings of early settlers from the East.) Proclaiming his intention to create a farm, Flagg also noted that “[t]he roots of the grass” were so “very tough” that “it generally requires 3 yoke of oxen or six horses to plough up the prairies … , but this is all that is done excep [sic.] fencing to raise a crop. After one year,” he added, “the ground is mellow and requires but a light team to plow it.”((Barbara Lawrence and Nedra Branz, eds., The Flagg Correspondence: Selected Letters, 1816 – 1854 (Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986), 16.)) To “break” his Prairie, Flagg used a cast iron plow with a wooden mouldboard. After 1839, the Prairie fell before the slicing action of new technology, sharp steel plows pulled by only two horses. Its conversion to “mellow ground” and its virtual disappearance occurred in a matter of decades. By 1860, oxen no longer appearesd on county tax lists of taxable property. Instead, farmers listed numbers of workhorses and mules. The rich soils of Madison County now produced excellent crops of marketable apples, peaches, and pears, as well as bountiful harvests of winter wheat, corn, and hay made from non-native grasses. In the pastures around Fosterberg and Highland, dairy animals feasted on non-native pasture grasses. Fences marked the end of common grazing grounds for neighbors’ cattle, horses, hogs, and sheep.

A restored prairie on the grounds of SIUE in 2015

Photo by Ben Ostermeier

Wildlife also disappeared. Robert Aldrich and his brother walked from Massachusetts to Illinois in 1816. Robert bought land northeast of Edwardsville after the survey in 1819. In 1860 he recalled that a surveyor told him that the last herd of buffalo had been seen in Madison County in 1811. Woodcocks and swans, birds rarely if ever seen in the area today, “abounded,” he wrote, until the 1830s. Elk “had become extinct” before he got to Illinois, but he had kept “a horn of one yet” that he had “found about the year 1823.” By 1860, bears and panthers were “rare.” Wolves no longer broke the evening’s silence. For a number of years Madison County paid bounties to wolf hunters. For example, in 1817, court records show that $137.75 was paid to the killers of 220 wolves. The Bounty Law, first enacted by the Territorial Legislature in 1815, was reenacted after statehood. Hunters had to present the scalp, “ears in tact,” to the County Court to claim their bounty.

The North American Gray Wolf was once common in Madison County. Because hunters killed wolves to protect commercially-valuable livestock, wolves are now extinct in the entire state of Illinois.

From Wikimedia Commons

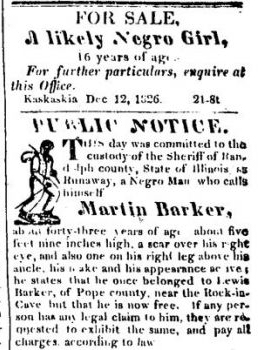

IV. Slavery in Madison County

Early in its history, Madison County was the scene of crucial struggles over slavery, the greatest public issue of the 19th century. Although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in all territories created from lands donated by the states to the federal government during and after the American Revolution, Madison County, like the rest of southern Illinois, was first occupied, ahead of the Federal Survey, by a majority of migrants with roots in the Southern States of Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, Kentucky, and Tennessee—all slave states. Some wealthier families brought enslaved workers with them into Illinois. As the Indiana Territory had done earlier, the Territorial Legislature of Illinois passed a law allowing owners of captive African-American workers to reclassify them as indentured servants, registering them as such at the county seat. In theory, workers entered into their indentures willingly, but in reality the terms of years were often so long that the servant would be dead or very elderly before completion of service. French slaveholders living in Illinois before The Ordinance of 1787 were allowed to keep slaves and their offspring. After Statehood in 1818, future indentures were supposed to be held to one year, but the long terms of many servants contracted before Statehood were to be undisturbed , and people enslaved before 1787 and their children remained “slaves.” Indentured servants were listed with horses and other property on tax lists. Penalties for running away were similar to those in slave states of the South. African Americans, moreover, could not protect themselves, their families, or any property they might have owned through the courts because a person of African origin, whether free, indentured, or enslaved in Illinois, could not testify against a white person in a court of law. Illinois’ “black codes” made African Americans second-class citizens. Ninian Edwards had brought with him from Kentucky in 1809 four enslaved persons whom he converted to servants. In the Census of 1820, Benjamin Stephenson, with eight servants was the largest owner of these contracts in the county.

An ad for a 16-year-old enslaved girl and a notice that a man who had escaped slavery was caught in Pope County, Illinois. Both were printed in the December 12, 1826 issue of The Illinois Reporter in Kaskaskia, Illinois.

From Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum

Edward Coles (1786-1868) is remembered in the history of Madison County as a slaveholder whose conscience turned him against slavery. From his father, he inherited 20 enslaved people whom he determined to set free. Circumstances and his family’s opposition forced him to delay his plan, but he did not give it up. In 1815, between missions as President Madison’s private secretary, he crossed the country, arrived in Edwardsville and bought 6,000 acres of public land east of Edwardsville on the Looking Glass Prairie. He returned again in 1818 and attended the Constitutional Convention in Kaskaskia, although not as a delegate. Then he returned to Virginia in 1819, and traveled back to Edwardsville with a number of the people whom he had inherited and made good on his promise of freedom. Although local lore emphasizes that Coles gave land, a quarter section, to each adult male among his former slaves, he did not provide them with capital necessary for creating farms on the land. Some were hired by Coles to work on his farm, while others had to seek a livelihood in St. Louis.

Portrait of Edward Coles

From Sketch of Edward Coles, Second Governor of Illinois, and the Slavery Struggle of 1823-4. (Chicago: Jansen, McClurg & Company, 1882).

President James Monroe appointed Coles to be the receiver of monies in the Federal Land Office in Edwardsville. In 1822, in a field of four candidates, he was elected Governor by a plurality, gaining 33 percent of the vote. Two of his strongly pro-slavery opponents together polled 59 percent. In his inaugural address, Governor Coles called for abolition of the indenture system, an end to the “black codes,” and freedom for the French slaves and their descendants. Responding to this, proslavery men called for a Constitutional Convention to convert the state into a slave state. Males across the state had to vote on the proposition to hold or not hold a constitutional convention in 1824. Madison County, as the most populous of the 30 counties existing in 1824, was a crucial battleground.

The election proved that Southern background did not dictate a man’s views on whether or not Illinois should be a slave state. Madison County’s largest family group in times after 1812 was the Gillhams, descendants of Thomas Gillham, an Irish Presbyterian who had settled in Virginia in 1790 and later moved to South Carolina. Among his many children a number moved west, first to Kentucky and then, to Illinois. The Gillhams lived in the populous Goshen Settlement, on the American Bottom southeast of Edwardsville. Although better-educated Yankees such as Gershom Flagg thought most of the Southern migrants were “ignorant,” in fact the Gillhams and other Southerners fully shared the New Englander’s desire to keep Illinois a free state. The county history of 1882 states that “[t]hough born in a slave state [the Gillhams] recognized the corrupting influence of slavery, and unalterably opposed its introduction into Illinois.” Gillham men and their kinfolk “almost in a solid phalanx, cast 500 votes against the proposition to make Illinois a slave state.”((Hoffman, 73.)) In Madison County, 563 voted against the Convention, while 351 voted for it. Statewide, the proposition went down 57 percent against to 43 percent for. Most of the men who voted against making Illinois a slave state did not support full citizenship for African Americans. Illinois’ “Black Codes” were not repealed until 1865.

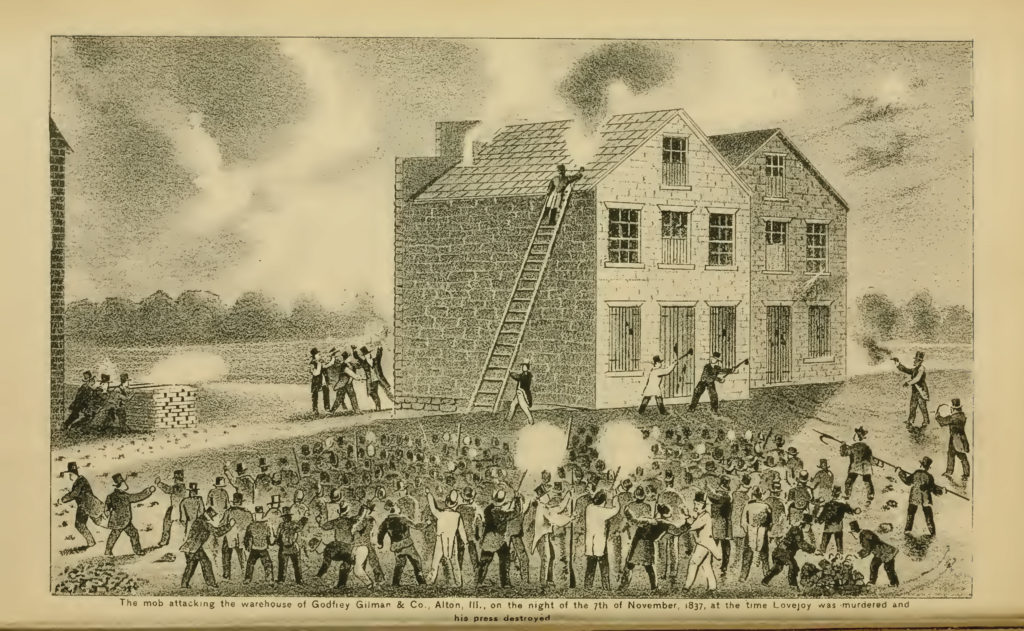

Artist depiction of the mob that killed Elijah P. Lovejoy

From Henry Tanner, The martyrdom of Lovejoy.

An account of the life, trials, and perils of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy (Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1881).

Madison County’s Alton gained national attention in November 1837, when a gang of “gentlemen of property and standing,” including Mayor John M. Krum (later Mayor of St. Louis), willingly participated in the murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy, an anti-slavery editor whose press had already been dumped in the Mississippi on two previous occasions. Lovejoy was not a radical abolitionist. He did not, for example, call the Federal Constitution a “covenant with death,” as had abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. He did not, like at Turner in Virginia, promote revolution among the enslaved people. Nor did he call for equal rights as had Edward Coles. Lovejoy had been a colonizationist and a militant anti-Catholic. But, except for about 60 supporters, all migrants from New England or the East, Lovejoy was seen by whites in the town as a colleague of Turner and Garrison, a threat to social order and the white men’s republic. No one was ever convicted of his murder. As the national debate over slavery grew hotter in the 1840s and 1850s, Lovejoy was often remembered as a martyr to the cause of “free soil, free labor, free men, free speech,” and as an example of the threat to freedom in a republic posed by powerful supporters of slavery.

V. Reform, immigration and impact of industrialization

By 1837 Alton was the fastest growing place in Illinois. With a population of 2,500, it was already known in the Mississippi Valley as a potential rival to St. Louis and a wholesale forwarding point for Illinois pork, flour, and whiskey to New Orleans. Between 1829 and 1832, 50 businessmen with capital to invest and numerous craftsmen flocked to Alton.

In 1831, Illinois abolished whipping, the pillory, and stocks in favor of confinement and hard labor as punishment for many crimes. Alton was selected as the site of the first State Penitentiary. It opened in 1833 with 24 cells. By 1857, when the prison was moved to Joliet, Alton’s building, with 256 cells, could hold some 500 prisoners. During the Civil War, it became a military prison. At times as many as 2,000 Confederate soldiers or sympathizers were crammed into its tiny rooms. Many died in this unsanitary hell: 263 in 1862, 623 in 1863, when smallpox broke out, 302 in 1864, and 274 in 1865. After the war, the prison was torn down. Only a small wall of limestone blocks remains today. By 1912, the site had become a children’s playground and a place for band concerts.((W. T. Norton, ed., Centennial History of Madison County, Illinois, and Its People, 1812 to 1912 — Volume 1 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1912), 240 – 244.))

The remains of the Alton Military Prison, 2014

From Wikimedia Commons

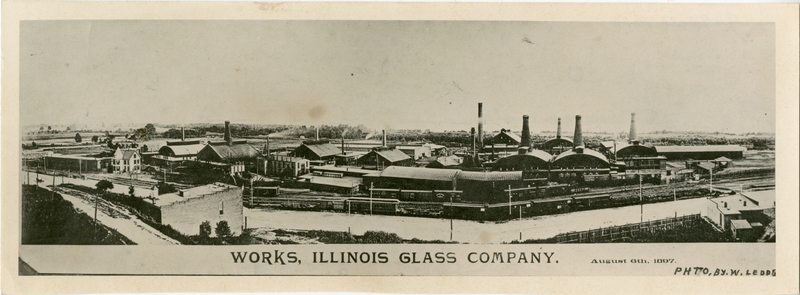

Abundant coal, wood, limestone, construction of railroads after 1857, first to Alton, and then, the bridging of the Mississippi in 1873, 1892, 1911 and 1928, drew capital and created a large industrial zone along the river in western Madison County. Factory towns–Madison, Venice, Granite City, Hartford, South Roxana, Roxana, Wood River, and East Alton–rose in the American Bottoms on former farms. Heavy industries manufactured steel, brass, glass, board and later cardboard boxes, farm equipment, kitchenware, railroad cars, automobile frames, machine tools, and refined crude oil. In 1928, Alton’s Owens-Illinois Glass works was the largest such factory in the world. New villages, such as Worden, Glen Carbon, and Maryville sprouted beside new coalmines and their railroad connections.

This panoramic photo shows works of the Illinois Glass Company in 1897

From the Alton Museum of History and Art

Since the first Federal Census of Madison County in 1820 counted 13,550, the population had always grown steadily, except during the depressed decades of the 1820s, 1880s, 1930s, and 1970s.

During the heyday of expansion in mining and manufacturing, county population increased by 64 percent, from 51,575 in 1890 to 143,830 in 1930. Most of this increase occurred in the urbanized areas. The county’s rural townships recorded a decline in population during the same period.

| Date | Population | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1818 | 4,509((Editor’s note: This census almost certainly did not include the numerous Native Americans living in northern Madison County at the time. Margaret Cross Norton, ed., Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library Volume XXIV, Statistical Series Volume 2: Illinois census returns: 1810, 1818 (Springfield, IL: Illinois State Historical Library, 1935), xxx.)) | |

| 1820 | 13,550((Editor’s note: Again, this census likely did not count Native Americans in Madison County. Additionally, Madison County’s borders still extended to the northern border of Illinois in 1820, which is likely why the population was so much larger only two years after the statehood census. Census for 1820 (Washington: Gales & Seaton, 1821), 157.)) | 201% |

| 1830 | 6,221((Editor’s note: Madison County shrank considerably to boundaries similar to its present shape in 1821, which is likely the main reason the population shrank between 1820 and 1830. Abstract of the Returns of the Fifth Census (Washington: Duff Green, 1832), 37.)) | -54% |

| 1840 | 14,433((Compendium of the Enumeration of the Inhabitants and Statistics of the United States (Washington: Thomas Allen, 1841), 86.)) | 132% |

| 1850 | 20,441((The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850 (Washington: Robert Armstrong, 1853), 702.)) | 42% |

| 1860 | 31,251((Joseph C. G. Kennedy, compiler, Population of the United States in 1860 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), 86.)) | 53% |

| 1870 | 44,131((Francis A. Walker, compiler, Ninth Census – Volume 1: The Statistics of the Population of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872), 23.)) | 41% |

| 1880 | 50,126((Statistics of the Population of the United States at the Tenth Census (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 57.)) | 14% |

| 1890 | 51,535((Report of the Population of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Part I. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 16.)) | 3% |

| 1900 | 64,694((Census Reports Volume I: Population Part I (Washington: United States Census Office, 1901), 17.)) | 26% |

| 1910 | 89,847((Thirteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1910, Volume I: Population 1910 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913), 106.)) | 39% |

| 1920 | 106,895((Fourteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1920, Population 1920 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921), 400.)) | 19% |

| 1930 | 143,830((Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population Volume I (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1931), 285.)) | 35% |

| 1940 | 149,349((Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940, Population Volume I (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1942), 295.)) | 4% |

| 1950 | 182,307((A Report of the Seventeenth Decennial Census of the United States, Census of Population: 1950, Volume I Number of Inhabitants (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), 13-12.)) | 22% |

| 1960 | 224,689((1960 Census of Population, Advance Reports, Final Population Counts: Illinois (Washington: Bureau of the Census, 1960), 3.)) | 23% |

| 1970 | 250,934((1970 Census of Population Advance Report: Illinois (Washington: Bureau of the Census, 1971), 26.)) | 12% |

| 1980 | 247,691((1980 Census of Population, Volume 1: Characteristics of Population, Chapter A: Number of Inhabitants, Part 15: Illinois (Washington: Bureau of the Census, 1982), 15-8.)) | -1% |

| 1990 | 249,238((1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Illinois (Washington: Bureau of the Census, 1992), 2.)) | 1% |

| 2000 | 258,941((Illinois: 2000, Summary Population and Housing Characteristics, 2000 Census of Population and Housing (Washington: Bureau of the Census, 2002), 52.)) | 4% |

| 2010 | 269,282((Illinois: 2010, Summary Population and Housing Characteristics, 2010 Census of Population and Housing (Washington: Bureau of the Census, 2012), 62.)) | 4% |

| 2016* | 265,759((“2016 Population Estimate for Madison County,” American Fact Finder, Bureau of the Census.)) | -1% |

French explorers of the 17th century had noticed coal deposits, and coal had been used for home stoves and steam engines in flour mills before the Civil War, but by the late 19th century, extraction of coal for both export and local consumption had become a major industry in the county, an industry enabled by rail links to local factories and to major manufacturers in St. Louis and other parts of Illinois. Shipping mines always adjoined a railroad. By 1910, 55 counties were producing coal dug from the gigantic bed underlying much of central and southern Illinois. Madison County, with 29 mines, 16 shipping coal to St. Louis or northern Illinois and 13 producing for local users, ranked 5th in the state, behind Williamson, Sangamon, St. Clair, and Macoupin. Miners in Madison County numbered 4,332 in 1910.

In Glen Carbon, largely owned by the Madison Coal Company and platted by the corporation in 1892, only a third of the 1,290 miners working there in 1899 listed themselves as ”Americans.” The rest, 805, were a mix of Germans, Italians, Bohemians, Polish, Irish, Welsh, English, Russian, Scottish, French Belgian, and Hungarian immigrants.

German and Irish immigration to Madison County had begun before the Civil War and continued after. Irish immigrants to Edwardsville and Alton had created Catholic parishes by 1849. German-speaking Swiss had platted the town of Highland in 1837, and it attracted German-speaking immigrants during the rest of the century. A famous Swiss patriotic anthem, Sempacherlied, was written by Heinrich Bosshard, who lived in Highland from 1851 until his death in 1871.

Even after Highland’s winter isolation was broken by the coming of the railroad in 1868, it remained a close, well-organized, park-like community surrounded by prosperous farms. Dialects of German could be heard in every venue and the schools were bilingual until later in the 19th century. By 1912, its population had stabilized at about 3,000. Other communities also welcomed German immigrants. Turnvereins, German social clubs, which often served as community centers, were found in many of the county’s villages and towns by 1900. In that year, about one-fourth of the population of Edwardsville had been born in some part of Germany.

Granite City did not exist in 1890. By 1910, its population approached 10,000. Neighboring Madison, also founded in the 1890s, with a population of 5,046 by 1910, was bigger than Edwardsville, the county seat. With Venice they formed what became known in the 20th century as the Tri-Cities. In contrast to manufacturers who were developing East St. Louis in St. Clair County, the Niedringhaus brothers, William and Frederick, who created Granite City from farmland between 1890 and 1893, tried to make it attractive to workers. They donated land for churches, schools, a hospital, a YMCA, and a city hall. The town was platted by a professional planner. For construction workers, mostly immigrant males, the brothers built a three-story frame hotel. They also planted 14,000 trees and supported in 1901 the organization of the Tri-City Labor Leaders Council, which represented 18 trade unions in the crafts. For these skilled “American” workers, Niedringhaus built 100 homes, made provision for sewers, built waterworks and a gas plant. Unlike George Pullman in Chicago, the brothers encouraged worker ownership of these homes and gave up their ownership of what became public utilities.

In 1895, the Niedringhaus’ St. Louis Stamping Company opened a large steel rolling mill and a stamping-enameling plant for Granite Ware, a famous brand of kitchen utensils and pans, which continued to be manufactured until 1956. Soon, Commonwealth Steel and the American Steel Foundry joined the original plants. Others followed. In Madison, the “Car Shops” of Madison Car and Foundry Company and the Helmacher Forge and Rolling Company filled the sky with the smoke of Illinois Coal.

County historians writing articles in 1912 for the celebration of Madison County’s Centennial did not dwell on the lives and experiences of the many southern and eastern European immigrants who were drawn to the industrial zones by the expanding job market. W.T. Norton, compiler and chief editor of the Centennial History, did observe that, in the Federal Census of 1900, foreign-born people and their children were a majority, by 3,393, of Madison County’s 64,694 inhabitants.

In Granite City, 1,200 Poles, Slovaks, Greeks, and Serbians had joined the workforce by 1904. These workers did not receive the amenities offered to their “American” counterparts. They were encouraged to settle west of the new town in the shadow of the steel mills in an area dubbed by other locals “Hungary Hollow” or “the foreign quarter.” After 1904, close to 8,000 Macedonian-Bulgarian men left families in Europe and arrived in “Hungary Hollow.” Only four families were part of this large migration to America. Most Bulgarians planned to return to the home country with money to support their wives and children, and many of them later did go home. Without a union, earning $1.50 per day of 12 hours, they tried to save $1.40 of every day’s pay. The men lived in large boarding houses, which could hold as many as 500 lodgers, or in cement-block three-room cottages with no indoor plumbing, called “boorts,” shared by up to 16 men sleeping in shifts as the mills ran for 24 hours. In 1916, during World War I, residents of “Hungary Hollow” renamed their neighborhood “Lincoln Place” to show their loyalty to the United States, a name it still bears.

After 1890 on a site south of Edwardsville, St. Louis industrialist N.O. Nelson, developed the Village of Leclaire. There, Nelson built facilities mainly for the manufacture of plumbing fixtures, marble tile, and custom installations related to plumbing. Disturbed by often violent confrontations between desperate workers and managers determined to control them, Nelson strove to create a haven for manufacturing where cooperation rather than conflict would characterize relationships between company officials and workers. To this end, a major feature of his plan for Leclaire was profitsharing, which strongly distinguished him from other corporate leaders, such as George Pullman near Chicago and the Niedringhaus brothers in Granite City, who also hoped to create smoother relationships between workers and managers. Unlike Pullman, who rented the housing he built and deducted the rent from paychecks, Nelson provided for worker ownership of individually designed homes in the village and for a cooperative store also owned by the workers. He built a school in the village and organized cultural opportunities and recreation for the whole community. Even his factory buildings were unique at the time, with huge windows providing natural light and with state-of-the-art safety policies. Nelson eventually moved on to other projects in other parts of the United States. In 1934, the village was annexed to Edwardsville, but it remains today a special neighborhood whose residents are proud of its place on the National Register of Historic Places.

The contiguous towns of Wood River, Roxana, South Roxana, and Hartford, located along the Mississippi north of Granite City and south of Alton, have been sites since the early 20th century for major oil refineries. Standard Oil opened the first plant in Wood River in 1908. It operated until the 1950s. In 1918, Shell Oil constructed a refinery in Roxana, which operated until the 1980s. The last refinery to be built in Madison County was Hartford’s Wood River Refining Company in 1918, which became Sinclair Oil in 1949, and Clark Oil in 1965. Increased use of automobiles and two world wars kept them going for nearly 80 years. The oil companies’ taxes supported good schools, and Shell itself built amenities in the area, such as a swimming pool, billed as “the world’s largest,” in the 1950s. After World War II, Shell Oil’s main research laboratory was in Roxana, and, including the refinery, the company employed close to 4,000 local people. The research section was moved to Houston in the 1980s, and Shell ceased refining oil in Wood River.

The Standard Oil Refinery shortly after its construction in 1908

From the Library of Congress

Even the mighty Mississippi was reformed by industrialization. Gradually potential damage from flooding was reduced, and the channel of the river was altered to accommodate barges full of grain, coal, oil, and other bulk commodities. Granite City’s Niedringhaus brothers tried with some success to protect their 3,500 acres by building their own levy in the late 1890s. In the flood of 1903 the city suffered some losses, but the major plants were safe. In 1912, construction of the Cahokia Creek Diversion Canal moved the Creek’s junction with the Mississippi to a spot 14 miles north of the historic outlet. During future floods, the engorged creek’s waters would not threaten industries below the convergence. Nearly five miles long, the canal was 100 feet wide at the bottom. Excavated earth was piled 50 feet back from the canal to form 30 miles of new levies. Between 1930 and 1940, the federally funded construction of Lock and Dam 26 on the Mississippi at Alton and the smaller 27 in Granite City created pools which made navigation of the Mississippi by barges possible almost all year. After many decades of service, damage to Lock and Dam 26 by the river’s scouring required that the structure be replaced. It was torn down and built after 1979 at a location two miles downriver from the earlier site. The main lock opened in 1990, and the entire project, named for U.S. Representative Melvin Price from Granite City, was completed in 1994. ((Norton; Rivers Project Office Website))

The original Lock and Dam 26 in 1940

From the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Digital Library

VI. Schools and Colleges

Agricultural and industrial wealth historically underwrote strong educational institutions throughout the County. By 1865, 86% of persons ages 6 to 21 were enrolled in a system of 119 public schools at a total cost to the County in that year of $39,432. A number of churches, especially Catholic and Lutheran, supported schools as well. By 1900, most of the major towns had high schools.

Shurtleff College, envisioned by its founder, the Baptist minister John Mason Peck, as a theological seminary and named for its principal benefactor, Dr. Benjamin Shurtleff, of Boston, opened its doors to male students in 1835 and to women, beginning in the 1870s. Shurtleff was the first college in the Mississippi Valley. When it stopped admitting students due to financial problems in 1955, the 50-acre Shurtleff campus was purchased by the State of Illinois as a temporary residential center for the Edwardsville branch of Southern Illinois University until a new campus could be constructed. Today, the former Shurtleff property houses the Southern Illinois University School of Dental Medicine.

This gate, installed in 1950 by the Class of 1950 of Shurtleff College, still stands on the campus of the SIU School of Dental Medicine in 2017

Photo by Ben Ostermeier

Massachusetts-born Benjamin Godfrey (1794- 1847), a veteran of the War of 1812 and formerly captain of a ship which engaged in the coastal slave trade from Baltimore to New Orleans, settled north of Alton in 1832. Godfrey built an empire in Madison County. He invested his considerable wealth in land north of Alton and platted what became, in 1840, the Village of Godfrey. Before the Panic of 1837, in partnership with a fellow New Englander, he managed a wholesale forwarding company from a warehouse in downtown Alton, which shipped the products of regional farms – flour, lard, meat, and whiskey – to New Orleans in exchange for tobacco, coffee, sugar, dry goods, and hardware. He was also a banker and early promoter of railroads. Godfrey, a born-again Presbyterian favored temperance. His conscience, possibly pricked by guilt stemming from his previous career as a slave-trader, put him in the camp of anti-slavery. He was also the father of six daughters, and he believed firmly in higher education for women, sharing the view of some reformers of the time that in a democratic republic, the role of mothers in raising their children to be good citizens was of paramount importance and required that women be educated to assume this role.

Godfrey’s carefully planned Monticello Female Seminary, with a three-year curriculum modeled on Yale University and a capacity for 80 students, opened in April 1838. Tuition was $9.00 for a 19-week summer term (April to August) and $11.00 for winter term (October to March). After nearly 100 years of successful operation, the Seminary in 1936 became Monticello College, a fully-accredited two-year liberal arts college for women. In 1970, as Monticello College prepared to close, the Lewis and Clark Community College District purchased the campus.

Madison County participated in the large expansion of higher educational opportunities that characterized Illinois and the nation after World War II. Although Lewis and Clark Community College had already enrolled its first 450 students in 1970, it officially opened its first campus on the Monticello College site in 1975. In 2009, it opened a second campus in Edwardsville in the spacious and historic N.O. Nelson factory buildings. In the 21st century, Lewis and Clark has major programs, such as community health and environmental studies, that respond to regional needs. For 16 consecutive years, up to 2011, Lewis and Clark showed the largest continuous growth of any Community College in Illinois.

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville opened its partially finished new campus, designed by the distinguished architect Gyo Obata, to 4,000 Juniors, Seniors and Graduate Students in Fall 1965.

A postcard of Lovejoy Library, named for the lynched abolitionist Elijah P. Lovejoy, on the campus of SIUE in the 1970s.

From Eastern Illinois University’s Booth Library Postcard Collection

Since 1957, students had been admitted to University classes at residence centers in Alton and East St. Louis. The completed campus, housed on 2,660 acres, was dedicated in 1967. SIUE in Fall 2011 enrolled 11,428 undergraduates and 2,289 graduate students.

Employment in educational institutions reflects the County’s transition to an economy based on services. In recent decades, Lewis & Clark and SIUE have ranked, with the public school districts, among the County’s largest employers. Lewis & Clark provides about 577 jobs, while SIUE employs about 2500 full-time people.

VII. Alton in Post-Industrial America

The City of Alton provides insight into the challenges faced by Madison County in the post-industrial era. One by one, the City’s largest employers closed their doors, beginning with Owens-Illinois, founded locally in 1875, which stopped producing glass in 1983, by which time it was an international corporation with factories in 24 countries. In 1998, the paperboard mill, Alton Box Board, also founded in the 19th century but now owned by the giant Smurfit-Stone Container Corporation, closed. In 2001, Laclede Steel, which had moved operations to Alton in 1915, and which had built artillery shells for the Allies in World War I, made steel used in the great dams built in the West by the New Deal, forged hulls for U.S. Navy ships in World War II, and produced the steel plates used to construct Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch in 1965, declared bankruptcy.((Susan C. Thomson, “Alton Comes to Grips with Industrial Decline,” The Regional Economist, October 2009, 16 – 18.))

Like many of Illinois’ fading industrial centers, Alton has chosen some familiar and sometimes controversial remedies as part of the search for jobs and a new communal identity. In 1991, The Alton Belle, Illinois’ first floating, cruising casino arrived at the river front. By 2009, it had been replaced by The Argosy, which remains stationary and no longer provides cruises. During two decades, revenues generated by gambling have declined. Yet, according to historian Susan C. Thomson, Alton’s share of the State taxes on the Argosy’s take in 2009 totaled $5,700,000, or 22% of the City’s operating budget. The City’s own per-customer tax on casino customers netted $414,000, which went into a fund for special projects. The promise of gambling to create jobs has not replaced the loss of other industries. In 2009, The Argosy employed 549 people, many only part-time.

Rebuilding of infrastructure has created some temporary work and made Alton more attractive to future employers. In 1994, the spectacular four-lane Clark Bridge, a project supported by both Federal and State dollars, replaced the narrow two-lane relic built in 1928. In 1996, the City used a five-million-dollar bond issue to fund a new marina for private boats. Part of the revenues have been used to pay off the bonds. The abandoned site of Owens-Illinois Glass, 144 acres, has become an industrial park managed by the City. Laclede Steel’s plant was purchased in 2003 by local investors in a small specialty mill, Alton Steel, which makes pipes, rounds, slabs, squares, and billets.

A Tax Increment Financing [TIF] District, including the downtown, the riverfront near downtown, and the riverfront industrial zone was enacted in 1994. The TIF funded the Marina, as well as a new amphitheater seating 4000 on the river front, which opened in 2009. (The occasion was a jazz festival dedicated to native Altonian, Miles Davis.) TIF has also supported new lighting, new walkways, construction of downtown apartments, renovation of historic buildings, and attractive plantings. By creating a TIF District, the City, according to Susan Thomson, “earmarks for development all real estate taxes collected in excess of amounts in effect when the district was created” in 1994. This kind of financing has also been used by other cities in Madison County, for example, Edwardsville, Collinsville, and Granite City.

The City also built a very visible Convention and Visitors Bureau, funded by a percentage of taxes on hotels, food, and drink. Bureau staff have focused on increasing history themed tourism. In 2008, Alton staged a well-attended re-enactment of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas’ famous debate of 1858. Three of the City’s neighborhoods full of buildings from the 19th century are on the National Registrar of Historic Places. In January and February of every year, “eagle days,” with guided tours of the scenic bluffs, attract thousands to watch the national bird diving and fishing in the River. Other groups in Alton are planning a Military History Museum and have created the Alton Museum of History and Art, located in an historic building on the campus of the Dental School.

VII. Mining the Vein of Historical Tourism

Other County towns have explored historical tourism. The village of Hartford, in 2010, opened a tower on the American Bottom west of town from which visitors can enjoy views of the confluence of the Missouri River and the Mississippi. The town of Roxana commemorates its history with The Wood River Refinery Museum. At the Melvin Price Locks and Dam, the U.S. Corps of Engineers maintain the National Great Rivers Museum, which attracts more than 10,000 visitors a year. Troy, original home of Senator Paul Simon, now hosts a museum dedicated to his career in journalism and Democratic Party politics, at the State and national level. Collinsville, whose coal mines had closed by 1940, maintains the Collinsville Historical Museum, and organizes an annual Horseradish Festival, commemorating a local specialty crop, and an Italian Fest, which remembers the Italian immigrants who helped to build the City. In Edwardsville, N.O. Nelson’s Leclaire School is now The Children’s Museum, while the 1820 home of Benjamin Stephenson and his wife, Lucy, is now the best-preserved Federal-style brick house, among only five surviving in the State. It opened as a museum in 2006, with period furniture and a goal of featuring information about the house’s other family, the Stephensons’ African American indentured servants. In 2010, African Americans, who have always played a role in the County’s history, created a monument to a significant part of Illinois history. On Edwardsville’s Main Street, they made Lincoln School, the town’s segregated grade school, built in 1911, into a memorial to a past of southern-style segregation and discrimination that many white residents of the County would prefer to forget. The mural covering the front of the building praises the education that students received from dedicated Black teachers at Lincoln School.

IX. Medical Services, Bedroom Communities, Environmental Awareness

Along with educational institutions, medical enterprises have created significant employment in Madison County’s new service economy. Anderson Hospital, which opened in 1977 in the former mining community of Maryville and which has more than doubled its original size, offers between 500 and 1000 part-time and full-time jobs in the 21st century. Gateway Regional Medical Center in Granite City, a descendant of the hospital founded by the Niedringhaus brothers in the 1890s, in the 21st century employs more people, 950, than the town’s one remaining steel mill. More than 800 people work in each of Alton’s two hospitals, Memorial and St. Anthony’s Health Center. St. Joseph’s Hospital in Highland, in the 19th century one of the first hospitals established outside of Chicago, employs about 300.

In the decades since 1980, many of Madison County’s towns have become bedroom communities for St. Louis. Godfrey, just north of Alton, is connected to Missouri via the new Clark Bridge, while Highland, Hamel, Worden, Troy, Maryville, Glen Carbon, Collinsville, and Edwardsville are conveniently located near to Interstate Highways, built in the last half of the 20th century. Edwardsville, was selected in 2011 by the national magazine, Woman’s Day, as one of the 10 most livable cities in America. Homes in Madison County, Illinois, have been marketed as part of suburban St. Louis, as “East County,” an alternative to the older suburban areas of St. Louis, collectively known as “West County.”

Greater environmental awareness, especially in the latter part of the twentieth century resulted in efforts to clean up the “brown fields,” acres soiled by industrial pollution in the formerly industrial areas of Madison County. That task goes on, as does the battle against air pollution, especially from coal-fired power plants and automobiles. Also, during the last 30 years, the Prairie regained some ground in this regional landscape. In Edwardsville, there are small prairie-covered acreages at SIUE and at the Watershed Nature Center, formerly the town’s sewer lagoon. Along the traction rights-of-way now bike trails in Glen Carbon are patches planted with prairie grasses. In Collinsville, the Collinsville Area Recreation District’s Willoughby Farm recreates for visitors the experience of life on a family farm in early 20th century Madison County. Visitors to Willoughby can explore a large vegetable garden, a segment of hillside restored to prairie, and a National Monarch Butterfly Waystation composed of plants native to Illinois. In Alton, The Heartland Prairie, a 29-acre restoration started by the Sierra Club in 1977, and maintained by volunteers and the non-profit Nature Institute of Godfrey, gives people of today a chance to walk through the tall grasses and brilliant flowers as they were seen by Gershom Flagg almost 200 years ago.

In 1912, 100 years ago, Charles Boeschenstein, born in Highland and a remarkably energetic and astute businessman, edited the Edwardsville lntelligencer. In a special issue of the paper, he announced a theme for the coming Centennial Celebration: “Madison County: Great in History, Agriculture and Manufactures.” In 2012, Agriculture, although now mostly on a corporate scale, remains important, with a production that now helps to feed the world. Manufacturing, in the way that Boeschenstein used the word, has ended. Yet, History remains, in its complexity, its sadness and its triumphal moments, as a way to bind us together, to give us understanding, and common ground. Madison County’s two centuries present relatively little that is unique, yet they might be read as an instructive microcosm of themes in the history of Illinois and America.